This first part of Mark Stocker’s fiercely intelligent celebration focuses on four singers, one famous, two obscure and one middling—but tragic. Common to each one of them is, surprise, surprise, an ability to sing…

There really was a time mid-century when a kind of infantile sexism prevailed in the popular music scene. We were supposed to thank heaven for “leetle girls” according to the creepy Maurice Chevalier. Accordingly, grown women were expected to record cute novelty records or, if they were more ambitious, inanely catchy ones. And then there were Christmas hits (shudder, Scrooge was right). I’m thinking of “How much is that doggie in the window?” (Patti Page) and “Me and my teddy bear” (Rosemary Clooney).

We can turn over the Page quite easily, but Rosemary Clooney—best known today for being George’s aunty—was a massive vocal talent. Her career had stops and starts and nearly came to premature ruin in the 1960s. Five children, the wandering paws of José Ferrer whom she married and divorced twice, alcoholism (Rosemary was probably pickled in the womb), and the capitalistic pressures of recording contracts and stardom (think Judy Garland) made Rosemary a remarkable, admirable survivor. She ultimately did it her way. I find her voice just as attractive as her legendary near contemporary Peggy Lee, and reckon she’s underrated in comparison. Give Rosemary the right material (almost anything by Rogers and Hart for a start) and you’re in for a treat. Ella and Sarah alike would have admired her—I just know it!

There are some 1950s goodies interspersing the trivia. Who can resist her duet with Marlene Dietrich, “Too old?” And there’s the tenderly sung “Tenderly”:

But Rosemary attained astonishing heights in what has become a cult album, the inanely titled “Love” (1963), where the impeccably curated material, superlatively delivered, nails it time and again. It’s the dream ticket, the sensuous orchestra of Nelson Riddle (with whom she was then conducting an illicit affair, just the conductor, mind, not the instrumentalists), which surely gives several songs their edge, and Clooney’s vocals: breath, pitch and phrasing to die for. Though recorded on the eve of Beatlemania, the record is 1950s in feel, which probably didn’t help its negligible commercial success.

The plus side of being conservative is that these songs exude repression and sublimation, and possess none of the “let it all hang out” vulgarity that still gives the 1960s a bad name. Some of the melodies are genuinely complex: am I alone in thinking that Marc Blitzstein’s “I wish it so” is possibly the finest popular song before “Eleanor Rigby?”

“Find the way” is very nearly as good, and if you like Rosemary at her more conventional, then Rogers and Hart’s “Yours sincerely” hits the spot too. Oh, you people, ‘Love’ should have been reciprocated but it was simply too good for you, you bought into the frothy Rosemary and spurned the one that had sheer class. Sometimes it is a case in music of “vox pop, vox dei” and stuff the snobby critics (early Beatles, Abba and Queen are prime examples), but here the populi still need consciousness-raising.

A long and horrible hiatus followed in Rosemary’s career: relationship and personal breakdowns, paranoia and barbiturate addiction, etc. But then, mirabili dictu, she emerged—in what was little short of the Clooney Renaissance—as a remarkably adroit, fully-fledged jazz singer, her deeper voice enhanced by her committed packet a day smoking. (Clooney’s voice and the tragic impotence of a snooker player while your opponent piles on the breaks are the two justifications I can think of for cigarettes).

Almost anything from about 1978 to 1998 in Clooney’s repertoire is worth listening to: her tributes to Duke Ellington, Johnny Mercer and of course, Rogers, Hart & Hammerstein. The first two tracks of RH&H, “Oh what a beautiful morning” and the witty duet “People will say we’re in love” (with fabulous trumpet AND vocals from the Louis Armstrong soundalike Jack Sheldon), make this probably the most awesome start to any album I’ve heard, and the rest doesn’t disappoint either:

Rosemary, I salute you. Yours sincerely (groan!), Dr. Stocker.

My next two singers, Lana Bittencourt and Miss Toni Fisher, are more minor stars but all the reason to resurrect them and share my guilty pleasures. As in art history, I relish the obscure. Lana who? Well, she was Brazil’s biggest female vocal star in the late 1950s, and even appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show. Her voice was big in the truest sense, and there was no point in resisting it.

Aldous Huxley divided the female sex into egg whisks and chests-of-drawers in the brilliant Point Counter Point, and Lana was emphatically an egg-whisk.

One Valentine’s Day, I sent a number of select fair-sexed friends her biggest hit, the passionate cover of “Little Darling” and their response was one of startled pleasure and perhaps affectionate reproach: how come I haven’t heard of her, “Little Darling” indeed!, etc. Listen and yield to Lana:

Her versatility is demonstrated in this clip from the eminently forgettable B-movie Jeca Tatu, about an endearing, lazy simpleton who has his property threatened by an unscrupulous landowner, and we all know how that will turn out. In the god-fearing society of that day in these rural parts, everything naturally stops with the Angelus bell. Note the guest appearance by Frida Kahlo (I know, I’m kidding), irritated by a fly:

Lana Bittencourt recorded admirable cover versions of “I will follow him” and, particularly, the impassioned “Johnny Guitar,” the title track of a Nicholas Ray film marginally superior to Jeca Tatu. You don’t need to translate from the Portuguese—in fact it’s a lot less risible than Lana’s hopeless English accent. Indeed, it’s a worthy rival of Peggy Lee’s far more famous version:

I’m looking for a culture anywhere on Earth that respects and preserves its sense of history, but it’s proving a vain search. My heart sank into my Doc Martens when I saw that the Israeli government hadn’t intervened to buy the archive of the “Roaring Lion” sculptor, Abraham Melnikoff, passed in at auction. Lana Bittencourt’s obscurity in Brazil today is almost as saddening. She’s approaching 90, and just a few years ago, was still bravely, albeit croakily, singing away…

Miss Toni Fisher (omitting her title is a no-no) had a brief but glorious recording career and it would not be ungenerous to pigeonhole her as a “two hit wonder.” But ‘wonder’ is the operative word. If Bittencourt’s voice is big, then Miss Fisher’s can break a Waterford decanter at 50 paces.

Her sole major US hit was “The Big Hurt” (1959). This is an irresistible combination of Miss Fisher’s vocals, pioneering electronic phasing sound effects and a winning melody. Not surprisingly, it became highly influential and was frequently covered, lending itself perfectly to big ballad treatment by Scott Walker, and exhilarating Northern Soul by the two Susans (Rafey and Farrar). But as often happens, the original version is the best:

Miss Fisher’s follow-up hit “West of the Wall” is a fascinating phenomenon, a rarity: a convincingly politicised song, recorded at a time of great international tension, the construction of the Berlin Wall. It’s on the side of angels:

A few “useful idiots” doubtless condemned it as anti-Soviet—which of course it rightly was. The singer’s passion matches the political indignation that millions felt. Possibly it wasn’t a big hit in the US because inane radio stations didn’t want music and politics to mix. This can, admittedly, be heavy-handed and irritatingly preachy (sorry, I’m no fan of John Lennon’s “Imagine”), but hardly applies here. Unlike so much noise that passes for music over the past half-century, Miss Fisher makes sure you hear and digest every word of her message:

West of the wall I'll wait for you

West of the wall our dreams can all come true

Though we're apart a little while

My heart will wait until we both can smile

That wall built of our sorrow

We know must have an end

Till then dream of tomorrow

When we meet again.

Tomorrow would only come in 1989.

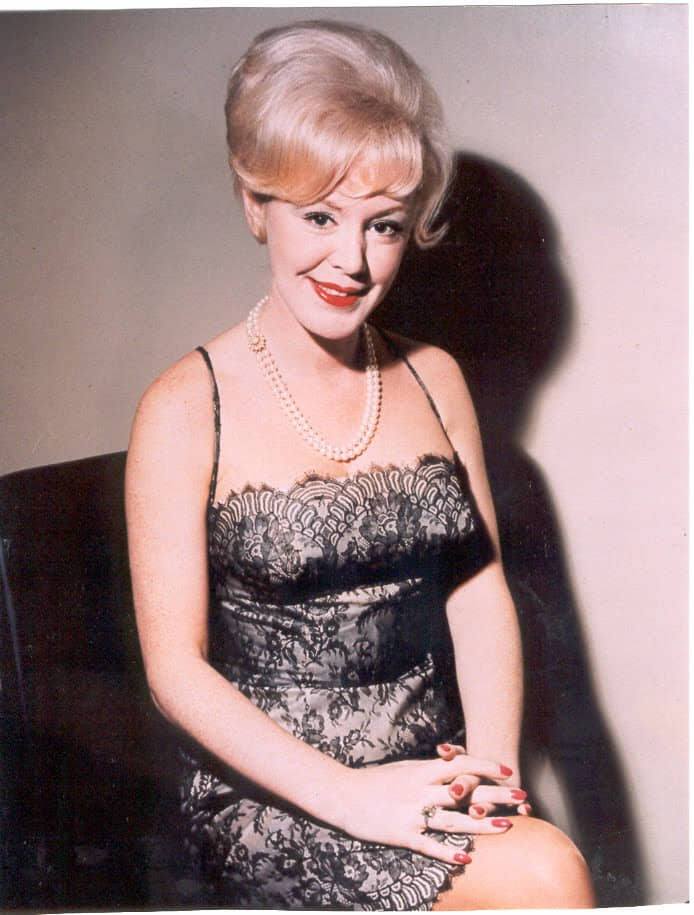

Imagine either the sex-symbol Jayne Mansfield, or her voluptuous British counterpart, Diana Dors, magically transformed from an actress into a singer. The result would surely have been Kathy Kirby (1938–2011). Tragedy is common to all three, the first two dying prematurely: Mansfield in a car accident and Dors of breast cancer, causing her grieving husband to commit suicide.

Kirby’s fate was if anything even crueller: a prolonged, squalid, impoverished forty-year coda to her relatively brief period of stardom. The Petula Clark hit “Don’t sleep in the subway, darling” inevitably comes to mind, and the ruined latter-day KK did just that. Or somebody’s doorstep.

But let’s focus for the while on the buoyant and radiating optimism that characterises the heyday of her recording career. The teenage, convent-educated (like Dusty Springfield and Marianne Faithfull) Kathy stood at the crossroads: she took singing lessons with view to becoming an opera singer, but fate intervened when she was discovered by band leader Bert Ambrose in 1956. She remained with Ambrose’s band for three years and he in turn remained her manager, mentor and lover until his death on stage in Leeds in 1971.

Like the previous two chanteuses, KK boasted a considerable vocal presence. Her material certainly lacks profundity (the early 1960s were shallow times, what with superstars like Bobby Vinton, Bobby Vee and Bobby Rydell in their pomp), but it hits the spot in joie-de-vivre and catchiness. “Dance on” was kept at the top of the charts for a month by those unsophisticated Australians across the pond; then there’s “Let me go, lover;” and KK’s admirable cover of Doris Day’s “Secret Love”:

Later KK verges on the dramatically camp, particularly the theme song for “Adam Adamant,” a nutty BBC series proposing that an adventurer born in 1867 and who had vanished in 1902 had been revived from hibernation in 1966. It provided a satirical look at life in the 1960s through the eyes of an Edwardian. Touché, Dame Shirley Bassey!

The fact that KK had a far grander voice than the younger and trendier Cilla Black and Sandie Shaw unfortunately failed to stand her in good stead. She was in her element in variety shows, not the Swinging Sixties, and by the later years of that decade had become rather “square.” Is it a sexist observation to say that wearing a dress below the knee in 1966 contributed to her fate?

While KK was regularly claimed to be the highest-paid female singer in Britain, behind the scenes things were falling apart. Her alleged affair with game show host Bruce Forsyth caused Ambrose to erupt into fits of jealousy. Kirby also realised that Ambrose, a compulsive gambler, had lost almost all her money. When he died she was both bereft and skint. I hate to say it, but like a number of far more celebrated stars (Elvis Presley, Michael Jackson to name but two), I fear KK just wasn’t very bright, and this when the playing-field was unquestionably tilted against women…

Turbulent affairs with both sexes ensued, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and survived on state benefits and meagre royalties for many years. She became a Garbo-like recluse before being moved to a nursing retirement home for entertainment professionals. This was at the behest of her niece, Sarah, wife of Margaret Thatcher’s son, the distinguished rally driver and Equatorial Africa coup leader, Sir Mark. A rare act of Thatcherite charity?! Lest I raise the hackles of some readers, I will soothe them with a lovely Kathy Kirby song, another standard (famously recorded by Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra, Dalida, etc.), “I wish you love”:

Listen to her, be touched by the generous spirits that this song conveys in spades, and posthumously wish Kathy blue-birds in the spring…

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.