Lounge Music, also known as Easy Listening, is considerably harder for an intellectual such as myself convincingly to theorise. It was—and remains—huge in terms of its popular impact and when these things were properly measured, in records sold. And yet there is a dearth of literature on it. This is music that is predominantly sung by solo male artists—though the lovely Dionne Warwick (pronounced Warrick, not War-wick, you plebs) eminently qualifies, as do a syrupy duo big in Britain in the 1970s, Peters and Lee. This is music that does not seek to problematise, nor indeed, does it follow that ambitious Marxist edict “the point is to change the world.” Au contraire, Lounge would claim itself to be apolitical and here I think it succeeds wonderfully.

Whilst you sip your Martinis or G&T in the golf clubhouse to the accompaniment of Frank Sinatra or, if the ambience is more trendy, Harry Connick Jr, you simply do not think about burning questions like the ordination of women priests or poor reading ability at lower decile schools—or even want to. Lounge is conservative, it does tend to reinforce the capitalist status quo, and, thank goodness, it doesn’t preach at us. Even fine people of the left (not an oxymoron) can and should derive comfort from Sinatra singing “Three coins in the fountain” or “Young at heart” in the background.

I like Lounge because it tends to be discreet; it doesn’t and shouldn’t aim to compete with the meaningful conversations I have enjoyed with friends sunk into deep hotel armchairs. I will go so far as saying that I even feel Frankie, Andy, Tony (Bennett), Johnny (Mathis, aka Mr. Velvet) Nat (King Cole), Matt (Monro) and indeed Engelbert (can’t spell his foreign surname, sorry!) are like friends to me.

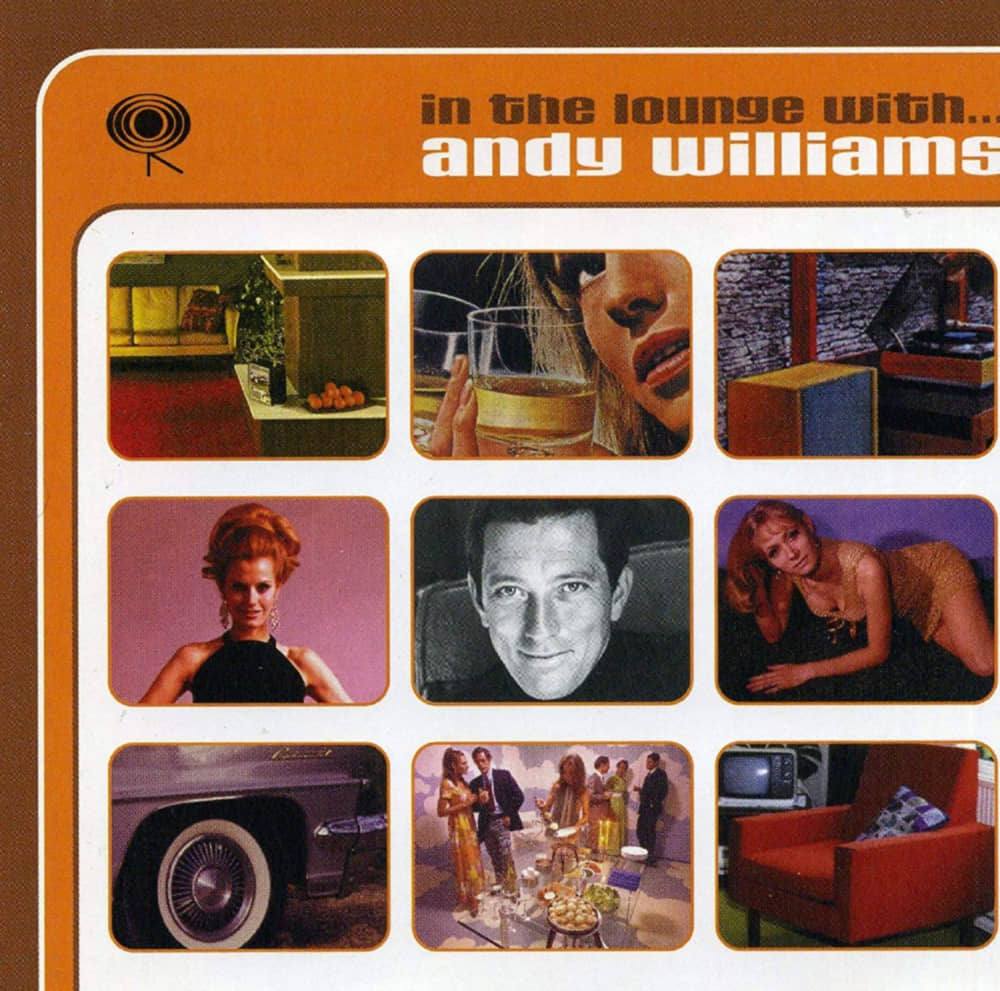

A pivotal figure in Lounge music is Andy Williams. In the last 30-40 years of his life I think he was criminally underrated, but he had the money in the bank, focussed on his art collection and sagely told us that he believed Obama was a grave threat (a rare venture of Lounge into politics). Above all, his music continued to give many people pleasure, which was always his aim. He was blessed with a fabulous voice, looks to match and a great choice in V-neck sweaters—some guys have all the luck.

But I love him for his witty self-reflexivity, when he called one of his late compilation albums, In the Lounge with Andy Williams. He would have been well over 70 at the time, and a comfortable armchair probably seemed more enticing than ever.

The songs are from his predictable repertoire, though “May each day” is sadly absent. How I loathed that song when I was a bolshie little 10-year-old and when it was played to death on Housewives’ Choice—’For Aunty Doris, who is 80 today,’ etc., with the compere sickeningly adding, “Bless her!” (Oh, sod off—it totally justified Punk Rock, but I digress!)

In older age, with maturity kicking in, I gave it another listen; and you know what, reader, I just melted and promptly forwarded the YouTube link to a few choice lady friends:

As the days turn into weeks, and the weeks turn into years,

There’ll be sadness, there’ll be joy, there’ll be laughter, there’ll be tears.

Of course, I now want the radio to play it when I reach 80. Andy, you have warmth, you shake hands with our hearts. But I concede that “May each day” isn’t exactly cutting-edge. Lounge rarely strives for such qualities, but every now and then a complex and fascinating song comes within its purview. I adore the pizzicato and clipped guitar of “Can’t get used to losing you,” and admire another lesser-known track with syncopated rhythms that make it veer towards a rock ballad: “Getting over you.” It’s also a fabulous production job, with perfect use of strings and chorus. I wish Andy had attempted something edgy rather more, but as I have implied, this goes against the fundamental grain of Lounge.

With anything half decent in Lounge, three things are vital: a professionally written song with that rarity these days, a compelling melody; a singer with a good voice; and capable production values.

Roger Chapman, of the Prog Rock band Family, who has a voice akin to barbed wire, would never have made it as a Lounge star, and probably “Chappo” wouldn’t have wished to anyway. His utterly different compatriot, Matt Monro (originally Terence Parsons, a cheery Cockney bus conductor), is probably little known to our predominantly US/Canadian readership, but there’s no question that he’s up there with the greats—his vibrato has balls alright!

Monro is a Lounge singer’s Lounge singer, and Sinatra himself recognised this, sending Matt fond wishes when the latter was on his premature deathbed (too many single malts in the 19th hole, poor Matt!) Our good friend Mrs Broadbridge wept when she heard he had passed away, but in her quick-witted way, quoted one of his loveliest hits: “Walk on, Matt!”

Sometimes Matt’s material could be jejune—he understandably disowned his 1964 Eurovision Song Contest entry, “I love the little things.” But given the right song, he was a Lounge killer: “Born free” and that art historian’s classic, “Portrait of my love,” with this delightful couplet: “Anyone who sees her/Soon forgets the Mona Lisa.” I rest my case.

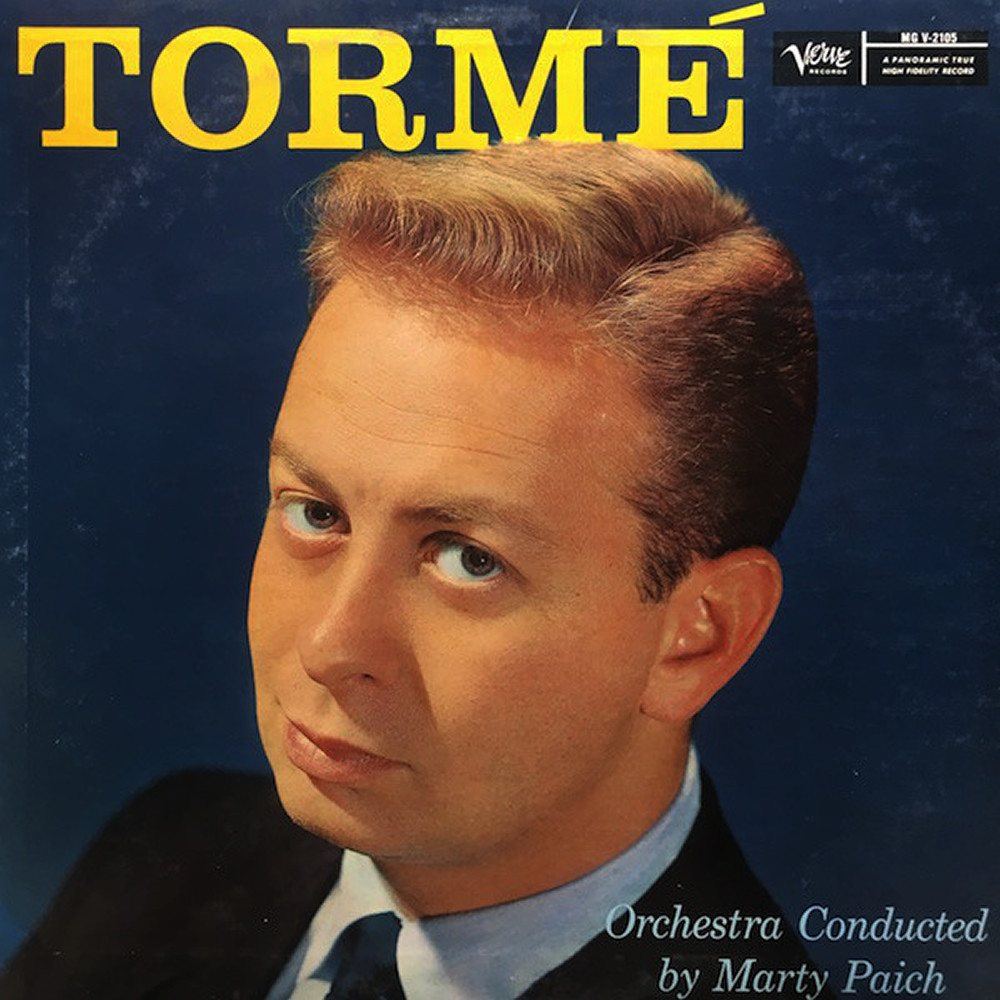

Lounge has its origins in Crosbyesque crooning, in the vocal refrains which were a charming part of Swing, and can sometimes be quite jazzy. Mel Tormé is emphatically in this category—too clever by half is Mel, sometimes downright parodic (as in “I’m hip”) and subversive. I fear he was a Democrat. Yet his version of “Polka dots and moonbeams” leaves the better-known one by Sinatra for dead:

I won’t harp excessively on Frankie and it’s not because he was personally obnoxious, but because I find something slightly cold and alienating in the very perfection of his voice. Yet he wins me over with the Sammy Cahn standards of the 1950s and later when he recorded the great Rod McKuen’s “Love’s been good to me”—so infinitely preferable to bloody “My Way.”

Tom Jones and Engelbert Humperdinck are two unquestionably significant singers who are Lounge related. Tom is best, however, when he aims at something soulful (I love his underrated cover of the Four Tops’ “Do what you gotta do”)—indeed, he’s the one improbable Lounge/ Northern Soul crossover.

Engelbert is the better Lounge suit fit though there’s a great deal of Country in him (“Ten Guitars,” “There goes my everything”). Even his signature hit, “Please release me” is emphatically Country in its origins. Gosh, this song brings back memories. Along with Rolf Harris’s nauseating “Two little boys,” it was one of the numbers I would sing in the school changing-rooms after swimming, and strangely was never beaten up as I attempted to do so. It is one of the best-selling British singles of all-time, and like “My Way,” was in the top 50 for over a year.

Its chief claim to fame was that it did the unthinkable: it kept the Beatles’ double A-sider “Penny Lane/Strawberry Fields forever” (and this is the Fab Four at their creative peak) off the number 1 slot. The sheer rage of earnest rock intellectuals over this catastrophe is still something to cherish, and it was reignited when I commented in the Guardian blog many years later: “Showed those long-haired vermin what’s what.” Indeed, it marked the triumph of Lounge (and mums and dads) over its upstart, pretentious rivals (Strawberry Fields Forever indeed), and I exult!

Lounge is more complicated than you think—just you try playing any Burt Bacharach melody on the piano: it’s much closer to Grade VIII than Grade I, and this genius of composer endows the genre with creativity and even profundity. When I was aged just 8 and Dionne Warwick’s Bacharach-crafted “Walk on by” was high in the charts, I really felt the sense of hearing something special and life-enhancing. Its infinitely sad message got home to me even then, but I was a precocious as well as an endearing lad. There are of course many other songs where that came from, notably “Trains and boats and planes” and “Close to you”—aah! Jimmy Webb snaps at the heels of Bacharach as a great composer.

I particularly like “The worst that can happen” (which was covered by the obscure Brooklyn Bridge), whose lyrics show Lounge in a rare but brilliant moment of emotional sadness:

Oh girl, don't wanna get married

Girl, I'm never, never gonna marry, no no

Oh, it's the worst that could happen…

Now, that’s the story of my life!

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.