Dr. Stocker hereby concludes his magisterial survey of favoured women singers…

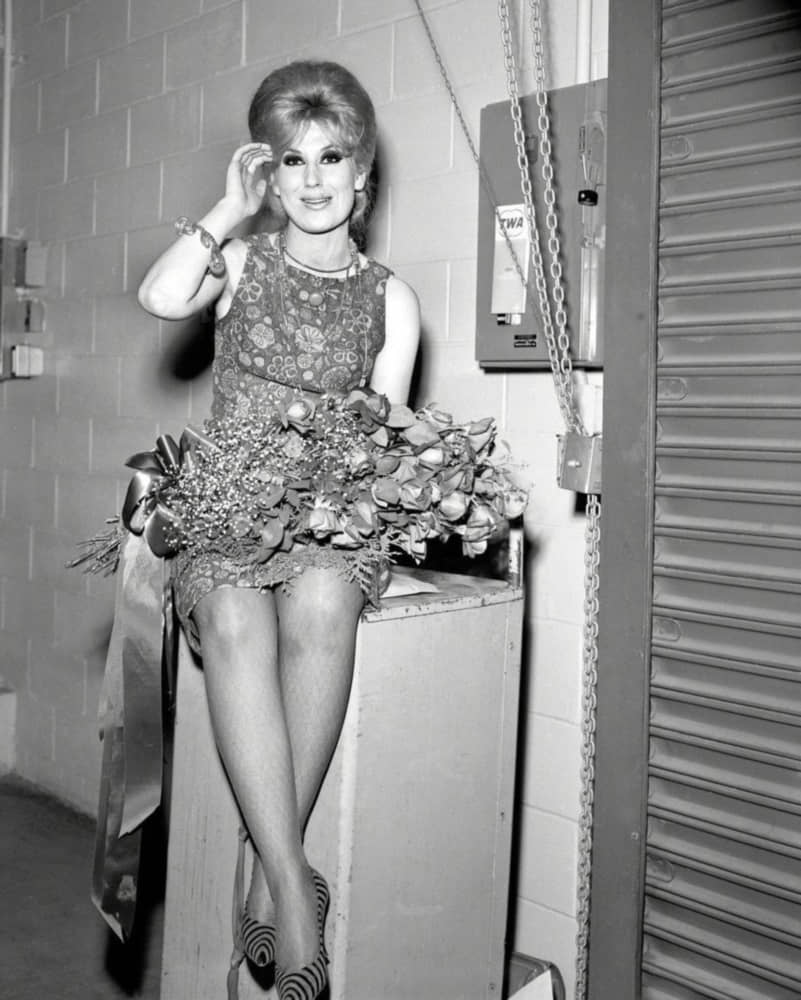

Riding high in the same Top Ten of January 1964 that included Gene Pitney’s “24 Hours from Tulsa,” whence my interest in pop music all started, was Dusty Springfield’s “I Only Want to be with You.” Though I wasn’t at all pro-girls at that stage in my almost eight-year-old existence—indeed thoroughly relieved to be at an all-boys’ school even if Mary Broad was no longer there to tie my shoe-laces—I nonetheless really liked both the song and the singer. With my discernment even then, I appreciated Dusty’s infinite superiority to Petula Clark’s contemporaneous, simpering, goody two-shoes “Thank You.” It’s cruel, I know, to put them head-to-head but history has utterly vindicated me:

Dusty posed a dilemma to me in this essay because, like Michelangelo, there is very little new or special you can say about her, but omitting her from my pantheon of girl singers would be unthinkable. So, it’s “Dusty definitely,” to quote an album title. She was arguably a more interesting character than her smarter, sassier contemporaries Aretha Franklin and Diana Ross. A white, middle-class British Catholic girl whose prime love was American black music—and whose voice sounded convincingly black—perhaps had a more fraught struggle to be understood and appreciated than those born in blue-collar Detroit into that ethnicity.

Franklin and Ross were/are emphatically establishment figures, tough to the point of ruthlessness and totally focussed. “There was only room for one Aretha” is a standout line in the film 20 Feet from Stardom, while Ross, probably not as naturally gifted as her fellow Supreme, Florence Ballard, made up for it by being an alpha female. Dusty by contrast had deep self-doubt, almost amounting to an imposter syndrome, together with a fiddly recording perfectionism that required her already remarkable voice to sound superb.

There were further paradoxes: she was by definition a public performer crippled with shyness, a sex symbol who was lesbian, a natural brunette whose stage persona and public image was a (dyed) blonde bombshell. People who don’t bother to look beyond her hairstyle write her off as being “fluffy”—which is precisely what they are. Dusty’s lengthy period in the US (1972–85) was mostly a tragic write-off; a Guardian writer mourned the “lethargy, paranoia, and drink and drug-soaked self-destruction that blighted her later years.” I for one was not convinced by her late-career resurgence aided by the Pet Shop Boys, though it cheered many sentimental hearts.

The best Dusty comes from the period spanning 1963 and 1969, culminating with her poorly-selling but now iconic album “Dusty in Memphis.” Not all of her many hits during this time were great songs (“Little by Little” endlessly repeated was little better than Lulu’s execrable “I’m a Tiger,” and it sounded like “Litterbug” to me). There were songs that I admired more than liked: “You don’t have to say you love me,” her sole British number one, to me always had a slightly dreary, Eurovision quality to it. But several were stand-outs: “Losing You” sounds as fresh as it did nearly 60 years ago; there’s the pretty, soulful “Wishing and Hoping” and “Going Back;” the more dramatic “My Colouring Book;” and above all “I Close my Eyes and Count to Ten”:

Its relatively complex melody requires several listens and accompanies a complexity of emotions. Dusty tells us what the object of her love is not: “It isn’t the way that you look/ It isn’t the way that you talk,” accounted for in a lower range. Rising up the octave, she explains: “It’s the way you make me feel/ The moment I am close to you/ It’s a feeling so unreal/ Somehow I can’t believe it’s true.” It’s as if Dusty feels she doesn’t quite deserve her lover, and when we link this to her dismaying lack of self-confidence and self-belief, the pathos is all the greater.

That voice! In 1978 she was in the midst of her American period decline and the nadir of her reputation but you’d never guess when she opens her mouth to sing a charming little trifle with her friend Rod McKuen, “Baby, it’s Cold Outside”:

The gay Rod is an unlikely seducer of the protesting, lesbian Dusty: what a hoot! And they were well aware of it, touchingly at ease in each other’s company and companionship.

When I was fourteen and we had a pleasantly laissez-faire maths teacher, Mr (“Randy”) Andy Funnell, yours truly and my friend Jeremy (not Black, he was no singer and was in Set 1 anyway) would not infrequently sing duets in the middle of lessons. The intention was to goad the prog rock or heavy metal-loving contingents in the class and it rarely failed. We were also, of course, budding humanities intellectuals: our tomfoolery could retrospectively be hailed as an ironising postmodern jeu d’esprit, avant la lettre, right?

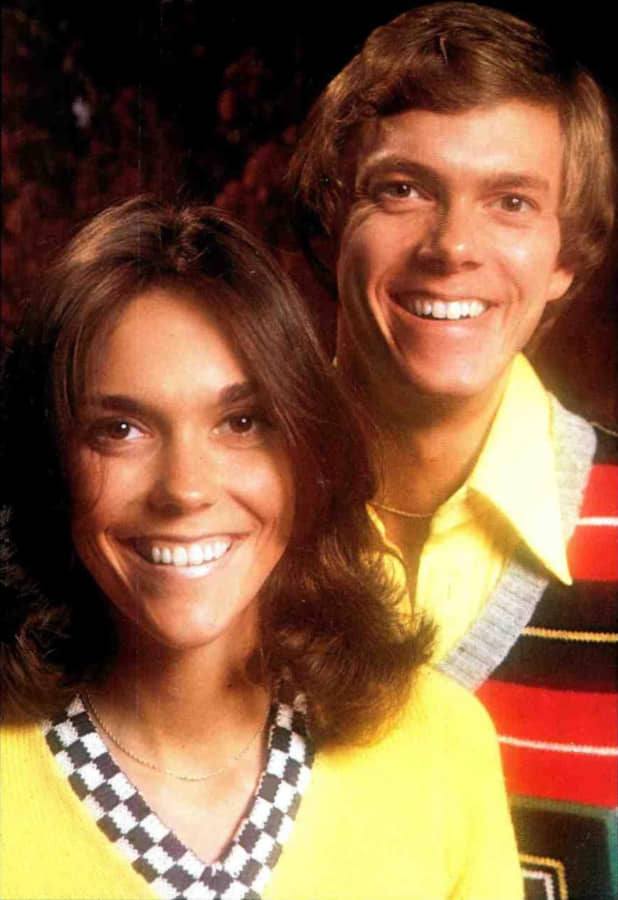

When we got a bit too operatic, Mr Funnell would tell us in bored tones to cut it out but it was good fun while it lasted. Elvis Presley’s “The Wonder of You” and the Carpenters’ “Close to You” were among our favourites. Elvis (at least in this song) I can now happily discard, but I’m still in love with ‘Close to you’. It’s a gorgeously melodic Burt Bacharach song, and when I first heard it, sung so faultlessly and with such perfect enunciation by Karen Carpenter, I knew this ushered in a fabulous new star:

Yet I still remain faintly irritated by the special ‘You’ that Karen feels close to: “Why do birds suddenly appear, every time you are near?/ Just like me, they long to be close to you.” A kind of Hitchcock in reverse, absurdly improbable, plausible with cats, dogs and even horses, but birds? Ducks, kestrels and swallows, hello! But I’m being literal-minded as ever, and everything else about the song and singer I forgive.

Karen and Richard Carpenter risked looking like a duo of goodie-goodies; with their wholesome appearance and wholesome musicianship, you’d swear that butter wouldn’t melt in their mouths. But time and again, the singers and the songs had the last word. Their choice of material was impeccable: the nostalgic and pensively sad “Yesterday Once More” (shooby-doo-lang-lang), the obviously happier “On Top of the World,” and the lovely Tim Hardin song, thoroughly Carpenterised, “Reason to Believe” are cases in point. Slightly more daring was the cosmic “Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft.” If you were such an occupant, then Karen and Richard would make thoroughly civilised earthlings to meet and greet you; indeed, Karen was at pains to assert in the song “We are your friends”:

Their music trod a tightrope between the charming and the sentimentally banal, but negotiated this masterfully, aided by their technical excellence. Richard, the marginalised male arranger and keyboard player, deserves considerable credit here.

Understandably, the Carpenters didn’t move too far out of an utterly pleasing, easy-listening genre. You wouldn’t expect Karen to suddenly start imitating John Bonham (of Led Zeppelin) on her drum-kit. She was a ‘good girl’ in the way that Patti Smith, Suzi Quattro and the underrated all-girl band Fanny were exhilaratingly bad. But she and Richard did once memorably depart from the tried and tested formula, shocking their conservative fans in the process. This was with the melancholy ballad “Goodbye to Love,” when Karen’s vocals yield to the almost Bach-like fuzz guitar solo of Tony Peluso. It’s truly groovy, and it excitingly bridged easy listening with the power pop genre of Badfinger and the Raspberries:

I’d really like to think Karen and Richard showed a sense of humour in their totally anti-climactic, indeed inane, follow-up ‘Sing a song’. “Ah! That’s the carpentry we want!” their core fans would have exclaimed.

Of Karen Carpenter’s appallingly brief life and dreadful death of anorexia nervosa, the less said here the better. Ars longa, vita brevis: Karen, thank you for being you. Oh dear, this sounds worryingly like a Carpenters’ song title, but I mean it!

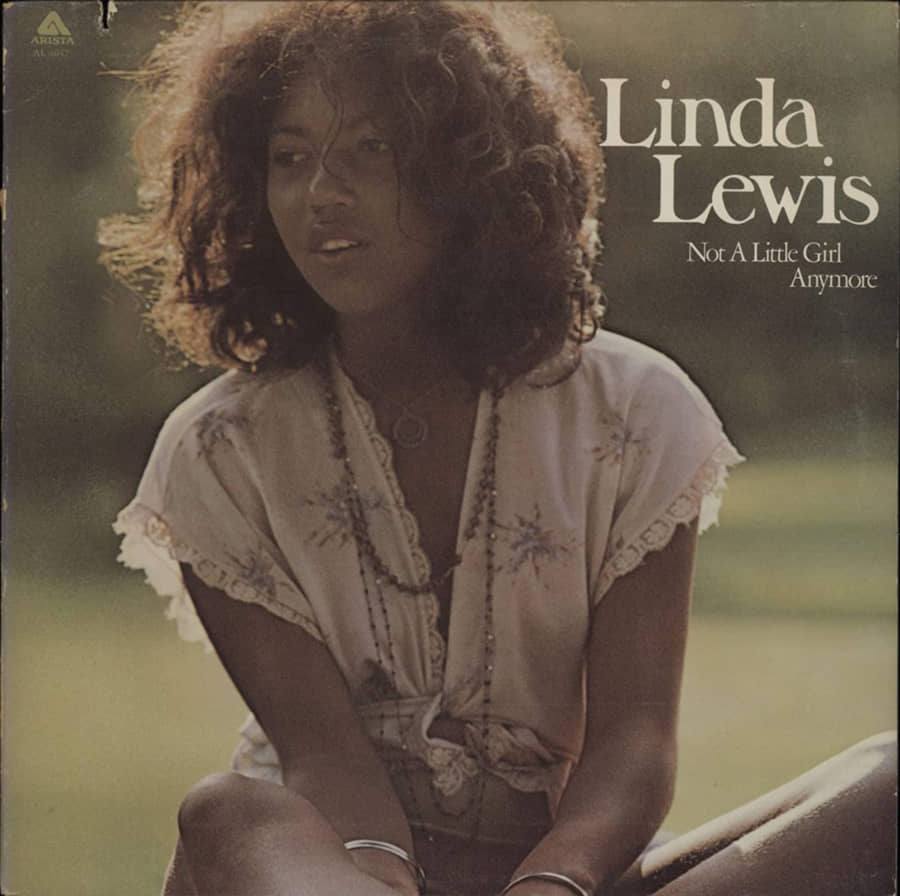

Linda Lewis is a far lesser known singer than Dusty or Karen but is the obvious bridge to Nina Hagen with her fantastic multi-octave vocal range. Here she’s surely the closest Cockney-Jamaican equivalent of the US one-hit wonder Minnie Ripperton (“Loving You [is easy ’cos you’re beautiful”]). Only Linda is infinitely less irritating, as she wisely refrains from imitating warbling birds. I admire her transition from precocious teenager to established (minor) star—the album title and content “Not a Little Girl Any More” says it all—and then to an amiable veteran/trooper at the Glastonbury Festival. Everything indicates that she has a regular, likeable and grounded personality: I envisage her in a late model Vauxhall, not a private jet and she may even vote Conservative.

It puzzles me, just as it does with Colin Blunstone, as to why Linda isn’t as big as she deserves to be. She’s nothing if not versatile: her first hit, “Rock-a-doodle doo,” which dates from her late teens, somehow combined the funky with the quirky, and I have to say rather annoyed me, clever though it was. I prefer the catchily retro “It’s in His Kiss” (her biggest hit, from 1975). I like her even more when her vocal pyrotechnics are intelligently utilised in “My Friend the Sun,” a cover of Family’s Prog Rock hit. I believe she was the then girlfriend of a member of that band (though not the barbed-wire vocalist Roger Chapman, that couple would have been altogether de trop):

She delivers Andrew Lloyd Webber with panache in “I’ll be surprisingly good for you” from Evita, and you believe her. But best of all is when she sings Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Moon and I” from The Mikado: try playing this end-to-end with Kate Bush’s near contemporaneous “Wuthering Heights” and I guarantee it will do your head in:

You see what I mean about versatility? I don’t think Linda did anything punk, so she has her limits. I suspect she was simply too accomplished to want to de-skill and regress, which is what that egregious genre demands.

Astute readers of these articles will have noticed that I always look for a consonance between melody and meaning in songs, and how I prize qualities of emotional generosity in the lyrics and delivery. I like this capacity in people (sadly, it’s not that common in academics) and I like it in music. The Linda Lewis song which best embodies this is the soulful “This Time I’ll be Sweeter”:

It’s very feminine, charming and manipulative: pleading and probably irresistible. Linda asks entreatingly: “Darling, can’t you see/ What losing you has done to me?” and then goes on to reassure him:

I'm not the same girl I used to be Have a change of heart Don't leave me standing in the dark Don't let confusion keep us apart Come back to me and I’ll guarantee All the tenderness and love you'll ever need. This time I’ll be sweeter Our love will run deeper I won't mess around I won't let you let down Have faith in me…

And “Darling” surely does!

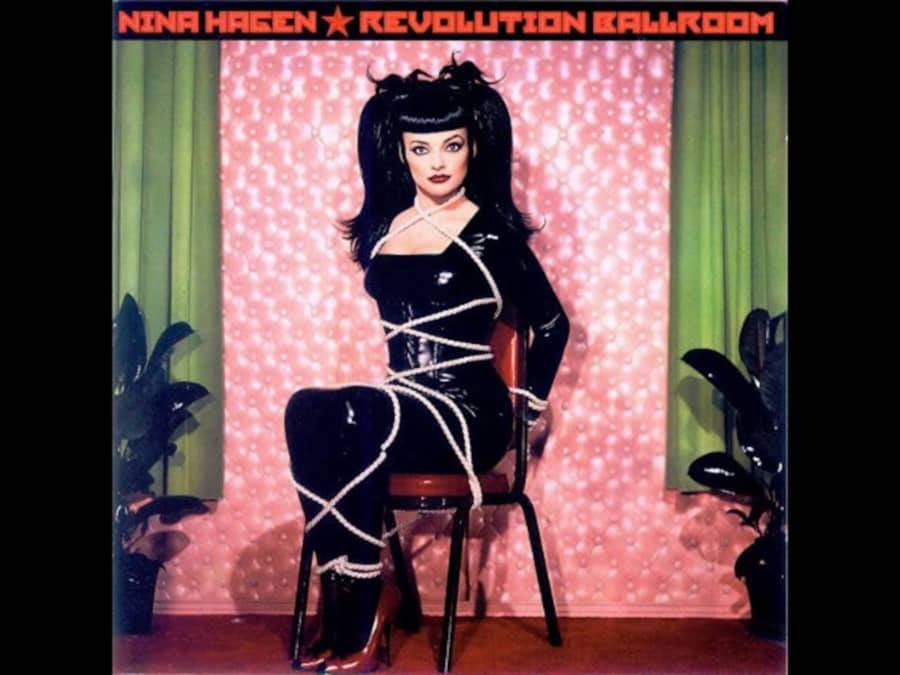

If the reader has detected a certain dislike of punk rock in my writings, let me correct them. A lot of it is horrid, and frankly aims to be precisely that. But its derivatives in not a few instances are terrific. Azure flowers emanated from the punk dung-hill: the Jam, the Clash, the Stranglers and particularly Squeeze (oh Glenn Tilbrook, you are Paul McCartney reincarnated). But the most remarkable punk and post-punk of them all is without doubt the German singer Nina Hagen. You can divide humanity into two categories: those who haven’t heard of her and look blank, and those who have—and who promptly grin and say “You would like her!” Like her? I’d do anything she asked me to do. I’d be like Anthony Powell’s horrible, obsequious Widmerpool and thank her if she stomped on me with her fish-netted legs and metal toe-capped Doc Martens!

Nina Hagen stands alone amongst all the singers I’ve examined so far in having exerted political influence—emphatically for the good. If the Berlin Wall crumbled, it was partly because Nina kicked it with those Docs. Her first hit as a teenager, “Du hast den Farbfilm vergessen/ You Forgot the Colour Film.” was a sly dig, mocking the sterile black and white communist state.

Her family were clearly too hot to handle for the authorities—her stepfather, the dissident singer Wolf Biermann, was paid the ultimate compliment of not being allowed to return to East Germany after a concert tour. In turn, the authorities did nothing to prevent Nina (and Mum) from joining him in Cologne, particularly after Nina threatened to become “the next Wolf Biermann” if they made her stay. Herr Honecker groaned: “We’ll be out of power in a month if we let her, and we can’t count on those trusty Soviet tanks!” (I made that up).

The nine-year-old Nina had been hailed as an opera prodigy and consider the year she went west, 1976: this marked the stunning advent of punk. Given its essential foundation of talentlessness, Nina ripped through punk like a knife through hot butter. Even the British, pioneers of punk and eccentricity alike, couldn’t quite believe what they saw when she took to the stage. Nina Hagen in her pomp was flamboyant, excessive, outrageous and courageous alike. Sometimes, just rolling her eyes, her ‘r’s or, ahem, her ass, she could transform herself within seconds from a Valkyrie Vampire or a Cruella to a clown—and back again.

If I stood any chance and could have Nina on my interviewer’s or analyst’s couch, baring her innermost thoughts and feelings, I would ask her this question: “Fraulein Hagen, underneath your lioness’s mane, your layers of punk makeup, all your velvets, leathers and frilly panties, isn’t there quite a shy girl lurking? Isn’t there a cashmere cardigan, string of pearls and a knee-length tweed skirt of a well-bred Bavarian Frau of ca. 1965 [Editor: exciting thought!] wanting to come out? Isn’t all your excess a carapace, a protection, from a diffident, introverted, softer and vulnerable Nina within? Don’t you in your heart of hearts wish you were recording beautiful songs like Joan Baez or Judy Collins?”

“Nein!” she would scream back, “Folk off, Herr Doktor!”

Now, let’s focus on the music—and unlike the largely prehistoric artists addressed so far, videos are integral to Nina’s appeal. Her choice of material, as you might expect, is scattergun, terribly hit and miss, probably numerically miss. And then you really need to get Nina in one of her relatively rare, subdued moods, not when she is showing off and wailing like a banshee, which is most of the time. She was not at her best when performing live by the recently toppled Berlin Wall in 1989, though we can readily forgive her glee. She’s far better when she’s acknowledging the very few sentient beings superior to Nina in her world view, e.g., the Blessed Virgin Mary:

If you played Mario Lanza’s impeccably sung version of “Ave Maria” immediately afterwards, it would appear a vapid, sanitised, 1950s anti-climax, underlying the cultural and historical need for Nina.

Her fans are split over “Hold Me”: some punk purists despise it as a sell-out to commercialism. I adore it. It’s a cover of legendary gospel singer Mahalia Jackson’s song. Listening to them sequentially underlines Jackson’s decent, boring worthiness, whereas Nina electrifies the song. I’d like to think of the Lord chuckling indulgently and a little nervously at her. In the very funny accompanying video she responds to an invitation from “Mother Mahalia” to perform her version and is aghast: “I can’t sing a [sic] gospel, I’m a white chick!” But she does:

And in her appearance Nina in 1989 resembles for all the world another Jackson: Michael. Can we rewrite history and posit the thesis that Jacko underwent all that cosmetic surgery in a doomed attempt to look like Nina Hagen? I know he was weird, but this is plain ridiculous…

Hagen’s humour resurfaces in the electro-punk of “So Bad” (1993). Sometimes she’s a bit worrying, a little too environmentalist/leftie/proto-woke for many readers. But here we should forgive her everything, especially when she rolls out all the baddies/bad things: “diet soda… user friendly… Helmut Kohl… the Yugoslavian rape”:

This is surely Chateaubriand’s romantic mal du siècle, 200 years on: go, Nina!

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.