Flash back to the mid-1970s. Was Britain’s intellectual nerve centre the Cambridge of Stephen Hawking and his black holes? No! Or Margaret Thatcher boning up on her Chicago economics? Warmer but no. Dear reader, ’twas the dancefloors of Northern and Midlands England where it was all happening: the rule of Northern Soul (hence the name). Its epicentre was the Wigan Casino – which was not a casino, while the Twisted Wheel in nearby Manchester was another Northern Soul mecca, as was the Torch Club at Tunstall, one of Arnold Bennett’s Five Towns and where I would now hang out at the Wedgwood Museum.

On those legendary soul “all-nighters,” talc was shaken on the floor to facilitate the glissando of the extraordinary dancers, an integral part of the Northern Soul aesthetic experience that complemented its aural delights and which anticipated the better-known break-dancing of a later era. And lest I put the cart before the horse, the music matched the dancers.

So, where did the music come from? Lonely Northern soul connoisseurs who could afford the airfares would go on quests to grungy US record stores and perhaps car boot sales to snap up rare vinyl, songs then going for a song but now often worth serious money, by the likes of Garrett Saunders and Susan Rafey.

Who? If you ask that, you haven’t lived… Well, to continue my story, the aforementioned connoisseurs would bring back their precious cargo and it would be played till it snapped, crackled and popped, to the delight of the Casino or Twisted Wheel regulars. They danced till the stars came home – or perhaps till the arrival of HM’s constabulary, no doubt in search of minute quantities of cannabis, not in itself particularly conducive to dance-floor aestheticism or athleticism.

I consider these Northern Soul connoisseurs the equivalents, nay, the superiors, of, say, Pico della Mirandola and Marsilio Ficino, hunting down their priceless classical texts 500 years earlier. And their patrons weren’t poncy Renaissance princelings in tights like Lorenzo the Magnificent, but the white working-class heroes and heroines who took to the talced floor and, as I say, danced away the heartaches of their humdrum lives. This cultural appropriation of obscure vinyl was surely akin to Palladianism, that distinctively English take on a great Northern Italian architect, but whereas Palladianism is posh (like Lorenzo), and formed part of one’s liberal education, Northern Soul is triumphantly proletarian and regrettably did not.

I was a gormless, liberally-educated posh boy when it was in its pomp; I had barely heard of Wigan Casino and nearly 50 years on I bitterly rue one of life’s missed cultural opportunities. But an “all-nighter” would have finished me off – I would have wanted my cocoa by midnight, or 1 a.m. most definitely. And it would have been a logistical nightmare: getting to Wigan from Cambridge would have probably taken over 6 hours, involved numerous changes of train and bus, and left me with little change from £20, which sustained me for almost a week in those days. I would have had to ask a suspicious mater and pater for more, when I should have been writing my next essay. Stocker the swotter. Shucks!

Old American records that matched the genre but had flopped commercially ten years earlier, their singers long retired and now probably cleaning houses like Darlene Love at her lowest ebb, suddenly became gold dust. As for the bemused artists – well, I certainly hope they were chuffed. To be a Northern Soul star, it positively helped to be a miffed miss and a slipped disk and not, pray, a chart hit. Northern Soul eschewed the mainstream: it studiously avoided the cloyingly commercial, such as “Reach out and touch somebody’s hand” by Diana Ross. As the author Anthony Burgess memorably replied, “I’d rather not.”

Diana just didn’t get it when she dissed Northern Soul as not being very good in the first place. It was uneven, sure, but it had an emotional generosity that transcended any shortcomings in musicianship. And sometimes its production values, perforce very economical, can make the outcome all the more moving. Give me the kitchen utensil percussion of Susan Rafey’s “The Big Hurt” any day in preference to a slickly professional Motown production of c. 1970.

Yet there were some Northern Soul chart hits, and I love many of them. Probably the best known is (the white Jewish) Len Barry’s gorgeous “1-2-3.” I still feel a thrill when I hear the recitative – and philosophy – of Len to the accompaniment merely of drums:

Baby, there’s nothin’ hard about love

Basic’ly, it’s as easy as pie

The hard part is livin’ without love

Without your love, baby, I would die!

A more minor hit-maker was Donnie Elbert; his version of the Four Tops’ “I can’t help myself” is exhilarating, his desperate tenor matching the emotional tenor – he sure cannot help himself, o sugar pie, honey bunch!

Then there was the slightly bigger R. Dean Taylor, a white Canadian(!) artist, whose “Gotta see Jane” is – like a lot of the genre – disturbingly obsessive, even menacing, and sounds as it’s been sung through a megaphone as Taylor relentlessly motors through wind and rain, destination wrongly forsaken lady love. The same singer’s hit “There’s a ghost in my house” with its stop-start rhythm would make the vast dance floor cast of Northern Soulsters go collectively bonkers.

But, I repeat, most Northern Soul worth its salt was “top of the flops” territory, as in the delectable girl group The Poppies’ “There’s a pain in my heart” (a nice juxtaposition with “There’s a ghost in my house”) which sadly failed to match the stunning chart success of its predecessor, “He’s ready” (Billboard #106).

A pain in my heart. Yes, even an up-tempo number like this reveals the emotional scarring and tragedy that is the sine qua non of so much Northern Soul, love’s agonies, not its ecstasies. It wouldn’t surprise me if the big-voiced Garrett Saunders blew his brains out after singing “In a day or two,” by which time shallow friends try and reassure him he will have recovered from disappointment in love.

Women singers could pile on the agony superbly: I think of Lorraine Ellison’s powerfully imploring “Stay with me, baby,” an anaemic cover version of which was cut by the normally admirable Walker Brothers. Then there’s the tragic Linda Jones, who died of diabetes aged 27 after failing to take her insulin. Her big hit (#74) “For Your Precious Love” scales alpine emotional heights and is justly esteemed by anyone with aspirations to Northern soulfulness.

Yet Northern soul can be happy, silly and sometimes today profoundly politically incorrect. Take “Girls, girls, girls,” when Chuck Jackson philosophises with a series of rhetorical questions, after confiding, speaking not singing, “Let me ask you something, fellas…”

What’s warm when the fire glows with glitter?

What’s sweet when all else seems so bitter?

What’s cold when your dreams start to wither?

And gives strength when you feel like a quitter?

Look to your heart when the trouble starts!

It’s girls this thing that I’m describing

Girls that make a man keep striving

Many shapes and sizes

Man’s greatest prize

Is girls! (girls) Girls! (girls)

Tell me, how many red-blooded fellows would not concur with Chuck’s sentiments? (Sorry, girls, I mean women…). Another, rather less loaded but joyous and celebratory Northern Soul classic is Robert Knight’s “The Power of Love,” which cheekily borrows its melody from Tchaikovsky’s “Marche Slave.” The Toys’ “Lover’s Concerto” – a bit too prettily successful for my liking – flagrantly borrows in turn from Bach’s Minuet in G major, which I was playing for my Grade II piano at the very time the girl-group were high in the charts.

But it’s the Toys’ less successful follow-up “Attack” that is far more Northern Soulful. Its changes of key and still more its lyrics, are unforgettable. I’ll treat you to the first couple of verses, and the plot thickens:

Once I walked beside you, so in love were we then

It had always been that way since we were children

Then one day she saw you, lied and flirted for you

Helplessly I watched her take your love away.

While she’s not with you she cheats and she enjoys to

How can I sit by and cry while she destroys you?

Though you may not want me, my heart keeps repeating

Onward, onward, time to stop retreating

Attack! Attack!

Awesome stuff, Northern Soul as emotional revenge. I wish Frankie Valli had recorded a cover with his famed falsetto.

Indeed, the genre is more than music, more than dance, more than a provincial British working-class cultural movement and, if you dare condemn it for colonialist appropriation, I can but pity you.

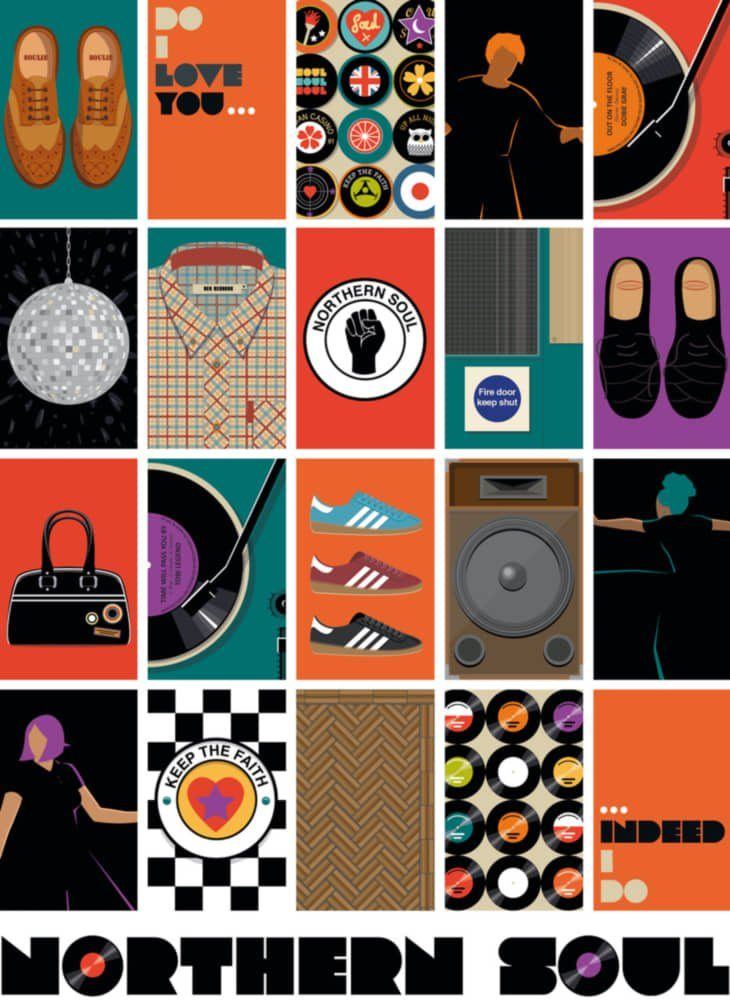

In its heyday and in its ageing aficionados’ hearts, it was something fundamental, a way of life, a faith. Lest we forget, its celebrated logo – itself a cheeky appropriation of the Black Power clenched fist – exhorts us to “Keep the faith.” Well, I’m a believer!

Dr. Mark Stocker is the resident Greek and Renaissance dance critic for the Postil Magazine.