In this article, Dr. Stocker promises to bring tears to your eyes—of laughter. Now, misheard pop music lyrics often aren’t normally subtle. But if a pompous and wordy commentary befitting someone with a Cambridge education is applied to them, adding a dash of autobiographical insight for good measure, then this constitutes the perfect guide to such a fascinating by-way of musicology. The majority of the lyrics are original mishearings, where Dr. Stocker alone is to blame, but a couple are better known and simply had to be included. Join him on his journey.

Misheard lyrics are on the one hand mere trifles that can be dismissed as being silly, but on the other they can be invaluable, particularly to the Freudian psychoanalyst, providing insights into one’s thoughts, feelings and love life that I never hitherto believed existed.

Perhaps my first memorable experience of such lyrics came not from me, but from my father, Oliver Stocker, whom I have written about before. He airily dismissed a lot of pop (“Here today, gone tomorrow!”) but like not a few middle-aged men in the 1960s, succumbed just a little to the charms of Sandie Shaw, a tall, skinny dollybird, who preferred to perform in her bare feet and had a very serviceable voice—though not a patch on Kathy Kirby or Dusty Springfield, mind.

Good, well-chosen songs, often by Chris Andrews (who almost certainly fancied her), provided hit material. Indeed, Sandie reached number one three times in the UK. The second such hit, “Long Live Love,” written by Andrews, chronicled a happy love affair:

I have waited a long, long time

For somebody to call mine

And at last he's come along

Baby, oh nothing can go wrong

We meet every night at eight

And I don't get home 'till late

I say to myself each day

Baby, oh long, long live love!

These are hardly memorable or profound lyrics. But they fascinated Mr Stocker, who told me: “This Sandie Shaw is a remarkable girl. She says of her boyfriend: ‘We meet every night at eight/And I don’t get home ’till eight.’ Now, pray, how is that possible?” (He talked like me, you see).

Well, it was indeed phenomenal; the bionic woman clearly had nothing on Sandie! I told Dad he was being silly. He told me I was being impertinent. Posterity, I think, has vindicated him.

Abba are wonderful; even that swinging historian Jeremy Black thinks so and has quoted the lyrics of their stunning debut, the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest winner, “Waterloo.” Yet Abba are Swedish; they are, let’s face it, foreigners. Their pronunciation of English, though far better than my Swedish, is faulty and unintentionally comical.

I don’t think humour comes easy to people of those Northern regions: Strindberg, Ibsen, anyone? Indeed, Nordic humour seems to centre on people doing idiotic things under the influence of the multiple glasses of schnapps that they down, to keep spirits up during their interminable winters. But precisely because Abba are being serious and earnest, they end up being doubly funny. “Dancing Queen” is arguably their most iconic hit. But the lyrics are forever creating linguistic problems.

The misheard chorus line “Dancing Queen/Feeling the beat of the tangerine” (tambourine) is merely silly. But when Abba start to become a little more ambitious in describing the disco ambience, they founder badly, especially the climactic passage where we are urged to “See that girl/Watch that scene/Digging the Dancing Queen.”

‘Digging’ is clearly meant in its informal sense, that of appreciation of this disco diva rather than anything horticultural or archaeological. But the change from the imperative “See/Watch” to the present participle is troublesome.

It is entirely understandable, therefore, that this has been rendered as: “See that girl/ Watch her scream/ Kicking the dancing queen.” Indeed, this would be a clinically accurate description of a working-class disco (perhaps infiltrated by angry, anti-Abba punk rockers) in late 1970s Britain; and Abba’s lines afford quite a poignant social insight thereof.

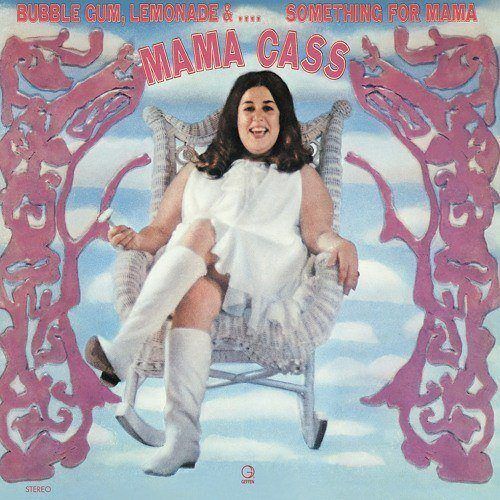

It is highly amusing when a song containing the customary platitudes about love is suddenly invaded by an incongruous outsider. I am not the only one who can testify to the ample talents of Mama Cass (Elliott) of Mamas and Papas’ fame.

“Dedicated to the one I love” is a song from the summer of love (1967) that I still cherish. She turned solo with some success before tragically succumbing to a heart attack induced by her obesity, aged just 32. Cass, blessed with that rich voice, and I suspect quaking laughter, was one big-hearted Mama. She could have done so much more.

One of her biggest solo hits was “It’s getting better,” a charming song written by the highly talented husband and wife team of Barry Mann/Cynthia Weil. The title itself would have appealed to the great optimists of history: Dr. Pangloss, Emile Coué and Boris Johnson.

Its message centres on the singer’s love affair that is more down to earth than extravagantly romantic, and there’s nothing wrong with that. As Mama Cass explains,

Once I believed that when love came to me

It would come with rockets, bells and poetry

But with me and you it just started quietly and grew

And believe it or not

Now there's something groovy and good

Bout whatever we got

And it's getting better

Growing stronger, warm and wilder

Getting better every day, better every day.

So far, so good. But the penultimate line is highly problematic. “Warm and wilder?” No, the great American writer “Thornton Wilder!”

But what on earth does this profoundly serious commentator on “the timeless human condition; history as progressive, cyclical, or entropic” think he’s doing, straying onto the set and disrupting Mama Cass’s homespun sentimentality? Were she to sing “Barbara Cartland,” it would be considerably more apposite.

Was she seeking to impress and go intellectually upmarket, or what? Heed your social station and your unsophisticated audience, Miss Elliott! Whoever will you be namedropping next, your namesake T.S.? Mr. Wilder’s sentiments thereupon (he outlived Mama Cass by a year) remain, alas, unrecorded.

Robert Palmer, like Mama Cass, died too young. A-pack-a-day (or more) smoker, he indulged in the terrible habit to give his voice a rasping power where needed. He was elegant, he was intelligent, he was kind: just listen to the humanity of one of his standards, “Every Kind of People,” and I defy you not to melt, if not to flirt dangerously with multiculturalism.

Palmer was above all, courageously varied and open to experimentation in his musical repertoire; very unusual in this regard, and all the more admirable for it.

From the blue-eyed soul of “Every Kind of People,” he could move into a convincing essay in proto-techno in “Looking for Clues,” to the Lounge genre in “Riptide” (Robert in his tuxedo), to—for want of a better word—the stylish sexism of his biggest hit, the multi-million selling “Addicted to Love.”

And then, in “Flesh Wound,” a little-known track on his “Riptide” album, we encounter Palmer the hard-rocker, a cigarette paper separating him from Heavy Metal. There was nothing that he couldn’t do. I had fond aspirations of his intellectual pursuits.

Palmer, one feels, would have enjoyed his Trollope and his Gide, and known his Rameau from his Rimbaud. In truth, according to his partner, he liked nothing more than getting up in the night and assembling model aircraft; shucks, one’s illusions were blown! But the music remains impressive, and it is to “Flesh Wound” that I wish to turn.

As befits the popular genre, Robert is intending to “pull the bird,” as it were:

We flew over miles of ocean, be prepared

I don't have the faintest notion, who'll be there

You underestimated, nobody sympathized

I think you'll soon feel better, once we get inside

I see the door is open, why don't we walk right in?

Let's put our party hats on, and let the fun begin.

It is when he is attempting to reassure his lady love, in his ardent courtship, that Robert comes to grief; she will “soon feel better.” Only I could swear he says “Zubin Mehta.” What on earth is he doing in the bedroom? Is this revered classical conductor going to make it a joyous threesome? (I hope I shock no reader who subscribes to this magazine’s wholesome family values, but do make allowances for the dubious morality of the rock music scene).

Worse, is Zubin a horrible voyeur? Did Mr Mehta seek damages from Palmer? A more charitable reading is that the namedropping of the conductor merely attests to the intelligently catholic range of music that Robert Palmer embraced. I would very much like to think that.

A wonderful misheard lyric is embedded within the signature hit of master rock guitarist and cult figure, Jimi Hendrix, “Purple Haze.”

Let me briefly digress: Jimi incongruously shared his birthday (27 November) with my great aunt, Miss Kate Henchman Stocker, MA (1895–1984), who taught English, Elocution and Drama to the grateful pupils of New Zealand’s most esteemed private girls’ academy, Samuel Marsden Collegiate School, Wellington.

In retirement, Kate rose to stellar heights in pteridology. Poor Jimi wouldn’t have had a clue. But to him, you and any other plebs, this designates the study of ferns, really quite a significant field in New Zealand. I definitely think this accident of birth made Aunt Kate more “groovy” than she could ever have believed, though when I told her this, she was decidedly nonplussed: “Who’s this man?”

To return to “Purple Haze”: in the lyrics, Jimi is, I think, holding forth upon the impact of nefarious substances, the liberal consumption of which, true believers swear, enabled his creative genius to thrive:

Purple Haze all in my brain

Lately things just don't seem the same

Actin' funny but I don't know why

'Scuse me while I kiss the sky

The last line is decidedly odd, but remember this was from the summer of love, when people in their thousands suddenly started behaving untowardly, particularly in the Haight-Ashbury quarter of San Francisco.

Famously, an alternative interpretation of the said line is “Scuse me, while I kiss this guy.” Now, that makes considerably greater sense, and is eminently consistent not only with the Zeitgeist of permissiveness, but with all the peace, love and whatnot that constituted such a vital part of the hippie ideology.

By all accounts, Jimi—author of “Electric Ladyland”—was joyously heterosexual, but perhaps he too was open to openness and experimentation. Yet it could still be “the sky’” and if the object of his attention had been a frilly “chick cloud”—to quote from an especially daft song by the Incredible String Band—then that would have made perfect sense.

Alternatively, yes, his lady love could have been “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Εὕρηκα, the perfect fit! Clearly there is method in Jimi’s hippie madness.

Readers may care to note that I received powerful intellectual vindication of my whole train of thought from the eminent linguistics expert (and poet), Emeritus Professor Koenraad Kuiper, who assures me: “The phonemic ambiguity of ‘the sky’ and ‘this guy’ is quite common and is disambiguated in context.”

Gee, thanks, Kon!

In retrospect, it is obvious that Herb Albert’s big hit, “The sky’s in love with you,” was a witty response to “Purple Haze.”

I will conclude this edgy, pioneering article with a reference to the gender fluidity that characterises our relativist age. In this regard, I sometimes use “It/Them” in my email and epistolary “signature” to confound and irritate woke folk, a proud assertion of my fundamental Otherness. But enough of this self-absorption.

Herman’s Hermits were a hugely successful pop group of the 1960s, part of the so-called “British Invasion,” led by the Beatles. Their success came partly because they were such a wholesome act, unlike the “long-haired vermin” that conservative folk would call the Rolling Stones, or the still-more egregious Pretty Things.

Lead singer Herman (aka Peter Noone) was a handsome, charming, youthful “boy next door” type, and with the Hermits enjoyed several US number ones, notably “I’m Henry VIII, I am,” and the poignant “Mrs Brown, You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter;” the latter sung in his broad, Mancunian accent.

A lesser-known hit by Herman’s Hermits was the jaunty, up-beat “Must to Avoid,” dating from 1965–66. It reached number 8 in the US, and number 6 in Britain. The lyrics commence thus:

She's a must to avoid

A complete impossibility

She's a must to avoid

Better take it from me.

Herman then goes on to explain: “She’s nothin’ but trouble/Better cut out on the double/Before she gets into your heart.” In short, she’s the sort of girl that your Mother would warn you against, unless that is your Mother is a hard-core feminist who joylessly objects to the systemic misogyny of this song.

The title poses a genuine problem. “Must to avoid?” A strange turn of phrase, and the early use of the verb ‘must’ as a noun would have made it even stranger nearly 60 years ago.

The alternative reading, “She’s a muscular boy,” makes infinitely greater sense. Clearly, Herman’s dangerous girl is transitioning, and avoidance during this difficult phase of her/his/their life is called for; really, this is sensitive counsel from him.

Alternatively, Herman might just have been alluding to those formidable East German women athletes who scooped up all the Olympic gold medals for tossing cabers, hurling garden gnomes and weightlifting, aided by performance-enhancing medication that deepened their voices. And what scary, hairy creatures they were, definitely to be avoided! This, though, is a more tenuous and frankly unsavoury gloss on an otherwise charming and innocuous song.

Indeed, perhaps after reading this, some sensitive souls are despairingly saying “Dr. Stocker is a must to avoid,” so he had better conclude.

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.