Foreword

Quite often post-war peace is fragile, having inside it the germs of future conflicts and confrontations. Too much attention has been given to the study of the causes and courses of the Napoleonic wars without equal attention having been given to those techniques which allowed nations to maintain peace effectively over a long period of time. Historians and policy makers such as Henry Kissinger, C. K. Webster, and Harold Nicholson have looked back at the post-Napoleonic era with some romanticism and have written of the “Concert of Europe;” or the years after the Vienna settlement as an era of peace and international order.

Certainly, the peace efforts of 1814-1815 helped provide Europe with almost a century of general peace, though no one asserts that absolutely no fighting or confrontation existed among the major European powers.

It should be acknowledge that the Austrian foreign minister, Prince Klemens von Metternich, the British foreign minister, Lord Castlereagh, and the Russian Tsar, Alexander I, should receive credit for devising a system which produced the long-sought peace after a generation of conflicts and social fractures produced by the wars of the Napoleonic era – thus establishing, even in an embryonic, contradictory and intermittent form, a system which guaranteed a mechanism of consultation and action, which allowed the European continent to move away, rather rapidly, from a long season of turmoil.

Controversial Peace And Reintegration Of France Within the Power System

1. The Vienna Congress: A Quasi-Inclusive Peace

The 1814 Treaty of Paris deprived France of her Rhine frontier, and she was reduced only to her boundaries of 1792, which in effect were her ancient borders, plus the significant additions of Avignon, Savoy, and several communes along the North and North-Eastern frontier. The terms of the treaty were lenient; the allies intended to avoid weakening the restored Bourbons or humiliating France so that Frenchmen could more easily accept the return of the Bourbons.

Considering Napoleon’s triumphant return from Elba, Liverpool’s announcement that the policy of 1814 had been a failure can hardly be called inaccurate. In an abrupt change from the lenient policy of 1814, the British Prime Minister proposed that the allies primarily focus upon their own security rather than leaving it to the Bourbons. “The French nation is at the mercy of the allies, in consequence of a war occasioned by their violation of the most sacred treaties. The allies are fully entitled to indemnity and security.”

Having begun in September 1814, five months after Napoleon’s first abdication, the treaty completed its “Final Act” in June 1815, shortly before the Waterloo campaign and the final defeat of Napoleon. The settlement was the most comprehensive treaty that Europe had ever seen; but it also showed how deep were the divisions between the winners (or major actors) – which behind a formal unanimity were, ijn fact, engaged in a bitter diplomatic fight.

Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Great Britain – the four powers chiefly instrumental in the overthrow of Napoleon – had concluded a special alliance among themselves with the Treaty of Chaumont, on March 9, 1814, a month before Napoleon’s first abdication. The subsequent treaties of peace with France, signed on May 30 not only by the “four” but also by Sweden and Portugal, and on July 20 by Spain, stipulated that all former belligerents should send plenipotentiaries to a congress in Vienna. Many of the rulers of the minor states of Europe put in an appearance, foreshadowing the progressively expanding G-8 to G-14 and other similar forums.

However, the “four” still intended to reserve the real making of decisions to themselves. Two months after the sessions began, Bourbon France was admitted to the “four.” The “four” thus became the “five,” and it was the committee of the “five” that was the real Congress of Vienna, which looked forward to the Council of the League of Nations, and more recently the Security Council of the United Nations.

Representatives began to arrive in Vienna toward the end of September 1814. Klemens Prince von Metternich, principal minister of Austria, assisted by Friedrich von Gentz, represented his Emperor, Francis II. Tsar Alexander I of Russia directed his own diplomacy, together with Karl von Nesselrode.

King Frederick William III of Prussia had Prince Karl von Hardenberg, as his principal minister, and Whilhem von Humboldt.

Great Britain was represented by its foreign minister, Viscount Castlereagh. When Castlereagh had to return to his parliamentary duties, the Duke of Wellington replaced him; and Lord Clancarty was principal representative after the Duke’s departure. The restored Louis XVIII of France sent Talleyrand, and after his resignation, sent the Duke of Richelieu, a former émigré.

While the official reason was to settle a comprehensive peace with France, the real agenda of the Congress included the disposition of Poland and Saxony (the major points of contention), resolving the conflicting claims of Sweden, Denmark, and Russia, and the adjustment of the borders of the German states. In general, Russia and Prussia were opposed by Austria, France, and England; however, the plans were submitted frequently adjusted, especially vis-à-vis France. It was often Austria and Prussia that were the hardliners against Paris, while Britain and Russia advocated a moderate approach, seeking as they did the stability of the entire continent.

Strategically, the strategy was as follows: Austria and Prussia wanted to establish a de facto protectorate over North-Central and Southern Germany as well as Italy respectively; France wanted at all cost the rapid and full reintegration into the major powers, with the highest possible rank of parity with others; while Britain, always looking for a balance of power in the continent, and was increasingly worried about Russia encroaching into the Southern Balkans and the Mediterranean Sea.

The inclusion of France put into the agenda of the Congress the re-inclusion of Paris in the Power system; and the brilliant action of Talleyrand exposed the differences among them (as he mentioned in a letter to King Louis XVIII). Despite the furious hostility, especially of Metternich, who planned just for a formal presence of France in the Congress, Talleyrand got the inclusion of French diplomats into several sub-bodies which supported the work of the main diplomatic body, similar to the Paris Conference of 1919 (namely, French diplomats now sat on the Commissions for Germany, for Switzerland, for Sardinia and Genoa, for the Duchy of Bouillon, for the slave trade, for the sea routes, for the precedence’s, for statistics and for the redaction of the texts of treaties).

The results of the action of Talleyrand were remarkable. Aside from the obtaining of the inclusion of France into the decision-making system of former enemies, he obtained the reinstallation of the Bourbons in Spain, Naples, and he saved the crown of the Prince of Saxony (the cousin of King Louis XVIII) from the aggressive policy of Prussia. Then, he reduced to minimal the border modification in France’s disfavour, and minimized the impact of a massive presence of Prussia on France’s Eastern borders.

All these points, which formalized the concept of war against Napoleon and not against France, however had a high price for Talleyrand, who was not able to limit the rapacity of the occupation forces in France (at least in the earliest time), nor affect the return of art looted by Napoleon, nor prevent the fall of Italy into a kind of Austrian protectorate (despite a presence of a Bourbon in Naples). These stood as points against him, together the opposition against the partition of Poland, which alienated the Tsar (against him, more than against France).

However, the desperate diplomatic battle of Talleyrand paved the road of his successor, the Duke of Richelieu, who was well acquainted with the Russians, having lived in exile in their country and having served in the Russian army and as governor of Odessa. The Duke was this better positioned, vis-à-vis the other allies, as he was an émigré, which gave him positive currency, and neither did his diplomatic efforts begin at zero as was the case with his predecessor.

But along with the settlement of a comprehensive peace with France, other diplomatic efforts began a hidden rivalry between Austria, Prussia and Russia, especially for Poland, which again stood divided among the three powers. Also, the reshaping of Germany meant that Prussia got two-fifths of Saxony and was further compensated by extensive additions in Westphalia and on the left bank of the Rhine. It was Castlereagh, who mediated this and who insisted on Prussian acceptance of this latter territory, with which it had been suggested the king of Saxony should be compensated.

The objective of Castlereagh was to have a strong Prussia to guard the Rhine against France and to act as a buttress for the new Kingdom of The Netherlands, which comprised both the former United Provinces and Belgium. Austria was compensated by Lombardy and Venice and also got back most of the Tirol. Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden on the whole did well. Hanover was also enlarged. The outline of a constitution, a loose confederation, was drawn up for Germany – a triumph for Metternich. Denmark lost Norway to Sweden but got Lauenburg, while Swedish Pomerania went to Prussia. Switzerland was given a new constitution.

In Italy, Piedmont absorbed Genoa, while Tuscany and Modena went to an Austrian archduke. Parma was given to Marie-Louise, consort of the deposed Napoleon. The Papal States were restored to the pope, Naples to the Sicilian Bourbons. Valuable articles were agreed upon for the free navigation of international rivers and diplomatic precedence.

Castlereagh’s great efforts for the abolition of the slave trade were rewarded only by a pious declaration. The Final Act of the Congress of Vienna comprised all these agreements in one great instrument. It was signed on June 9, 1815, by the “eight” (except Spain, which refused, as a protest against the Italian settlement). All the other powers subsequently acceded.

2. Congress Of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) And The G-8

The Congress or Conference of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen), held in the autumn of 1818, was primarily a meeting of the four allied powers (Britain, Austria, Prussia and Russia) to decide the question of the withdrawal of the army of occupation from France and the nature of the modifications to be introduced in consequence to the relations of the four powers towards each other, and collectively towards France.

The Congress, which looks forward to the revision conferences of the UN system, convened in Aachen on 1 October 1818. It was attended in person by Emperor Alexander I of Russia, Emperor Francis I of Austria, and Frederick William III of Prussia. Britain was represented by Lord Castlereagh and the Duke of Wellington, Austria by Prince Metternich, Russia by Counts Ioannis Capodistria and Nesselrode, Prussia by Prince Hardenberg and Count Bernstorff. The Duke de Richelieu, by favor of the Allies, was present on behalf of France, even if his presence was in reality part of the new political reality.

The evacuation of France was agreed upon in principle at the first session, with the consequent treaty being signed on 9 October. The immediate object of the Conference having been thus readily disposed of, the remaining time was taken up with discussions of what form was to be taken by the European alliance, and the “military measures,” if any, to be adopted as a precaution against a fresh outburst on the part of France. The proposal of Emperor Alexander I to establish a “universal union of guarantee” on the broad basis of the Holy Alliance, after much debate, broke down because of the uncompromising opposition of Britain.

Thus, the main outcome of the Congress was the signature, on 15 November, of two instruments: a secret protocol confirming and renewing the Quadruple Alliance established by the treaties of Chaumont and Paris (of 20 November 1815) against France, and a public “Declaration” of the intention of the powers to maintain their intimate union, “strengthened by the ties of Christian brotherhood,” of which the object was the preservation of peace on the basis of respect for treaties. The secret protocol was communicated in confidence to Richelieu; as to the Declaration, France was invited publicly to adhere to it. This sub-architecture, named the Quintuple Alliance, was the first of a long series of mutual and secret treaties of insurance and counter-insurance, which forcibly led the same powers to the first civil pan-European war, namely, World War One.

The Quintuple Alliance is largely perceived as the final moment of a path of reintegration of France into the power system and the end of the state of exception which marked the political landscape since the launch of the Vienna Conference.

What transformed the Aix-la-Chapelle Congress in a de facto European Summit, more and more similar to the Allied and Associate Powers after WWI with its huge agenda (e. g. the fate of the Kaiser Wilhelm II, Fiume, the borders of Albania, etc.), were the number of areas left unsettled in the hurried winding up of the Congress of Vienna; or those which had arisen since. Of these, the most important were the methods to be adopted for the suppression of the slave-trade, and the Barbary pirates of Maghreb and their activities. In neither case was any decision arrived at, owing mainly to the refusal of the other alliance powers to agree with the British proposal for a reciprocal right of search on the high seas and to the objection of Britain to international action which would have involved the presence of a Russian naval squadron in the Mediterranean.

In matters of less importance the Congress was, of course, more unanimous, such as, on the urgent appeal of the king of Denmark, Charles XIV of Sweden received a peremptory summons to carry out the terms of the Treaty of Kiel; the petition of the Prince-Elector of Hesse to be recognized as king was unanimously rejected; and measures were taken to redress the grievances of the German princes. The more important outstanding questions in Germany, e.g. the Baden succession, were after consideration reserved for another international conference to be called at Frankfurt/Main.

In addition, a great variety of questions were also considered, from the treatment of Napoleon at Saint Helena to the grievances of the people of Monaco against their prince, and the position of the Jews in Austria and Prussia. An attempt made to introduce the subject of the Spanish colonies was defeated by the opposition of Britain. Lastly, certain vexatious questions of diplomatic etiquette were settled once and for all.

The Congress of Aix-la Chapelle, which broke up at the end of November, is of historical importance mainly as marking the highest point reached in the attempt to govern Europe by an international committee of the alliance powers, even at the informal level. The detailed study of its proceedings is highly instructive in revealing the almost insurmountable obstacles to any really effective international system.

After Aix-la-Chapelle, the alliance powers met three more times: in 1820 at Troppau (Opava, Poland), in 1821 at Ljubljana, and in 1822 at Verona. Afterwards, a similar procedure, even if informal, was convoked in major conferences for specific themes and issues, e.g., the Berlin Conference for the Balkans (1878), the one for the West Africa (1884-1885), and the Algeciras Conference (1906) for Morocco.

Even after a destructive conflict, as was WWI, the setting up of a new, organic and complex architecture, the League of Nations, with a parallel sub-system set up by the “winners,” like the Allied and Associate Council (with the Ambassador Conference as operational arm and the galaxy of Committees in charge of many issues as the first was the controversial demilitarization of the Central Powers ), showed that the states were not yet ready to resign to their own sovereignty authority; and another destructive conflict, WWII, allowed for the set-up of a more effective one system, around a galaxy of organizations, that surround the globe with a network of agreements. Nevertheless, the risk of war remains ever-present for mankind.

In reality, this system, due to the absence of a permanent architecture and focused on a rotational mechanism, from a contemporary perspective, appears to have inspired the multiple systems which now proliferate (G-7, G-8, G8+5, G-11, G-14, G20 developing nations, G-20 major economies, G-33, G-77 plus China).

Demilitarization, Occupation And War Reparations – The New Elements Of Peace?

1. The French Demand To Reduce Foreign Occupation Troops

In July, 1815, the British Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, first suggested that the Allies place an occupation force inside now-defeated France. Liverpool deemed that the “magnanimous policy” introduced in 1814 had been a complete failure; and the allies agreed with British Prime Minister’s assessment. The dispatch of an allied occupation force of 150.000 troops for a period of five years, became a key element of the Allied policy towards France.

This was quite an innovative element of winner-defeated relationships, and would be frequently used in subsequent conflicts, such as, the American Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War, WWI and WWII. Of course, there were earlier examples of this procedure during the Napoleonic wars (e.g., the occupation by French troops of the Netherlands, Spain, Germany, Italy and Illyria, even though the institutional framework was different in consideration of the fact that these states were allied or annexed).

The issue was perceived as extremely unjust and politically counterproductive by the new French leadership, which, correctly, saw the occupation force as a formidable weapon in the hands of supporters of Napoleon, whose used it to show that the Bourbon dynasty, having just returned, was weak and not able to save the prestige and dignity of France. Thus, it became imperative to reduce the impact of this opinion, in order to build support for the monarchy (and insure the survival of the king’s government), Richelieu sought a reduction in the troop strength of the occupying army earlier than originally proposed by the allies.

He broached the subject with the Allies in the summer of 1816, barely a half-year into the occupation. Public order had been maintained, he told the occupying powers, France was paying the cost of the occupation; the local authorities were cooperative with the occupiers. Richelieu then pointed out the greater good that would be achieved if the Allies reduced the number troops – there would be a reduction of the cost of the occupation to France, and this would demonstrate the good intentions of the Allies, and this further would confirm their confidence in the French crown, the French people (and the Richelieu ministry).

Richelieu communicated his thoughts personally to the Duke of Wellington in a meeting on June 6, 1816. It was readily apparent to Richelieu that Wellington was the key to achieving a troop cut, and, if Wellington were convinced that a reduction was in order, the allied governments would surely accede to his decision. Wellington forwarded the message to his government, which convinced Richelieu that he had gained the field marshal’s unqualified support.

Richelieu also wrote to his old benefactor, Tsar Alexander I of Russia, expressing his hopes for a reduction, but without a formal request. According to the Treaty of Paris of November 20, 1815, the Allies agreed that the army of occupation would remain in France for a maximum of five years, with a review of the issue after three years. It was in France’s interest that the earliest possible departure date be secured. Perhaps more importantly, Louis XVIII and the Duke of Richelieu had vested interest in producing an early departure to demonstrate, just as they had with the partial reduction of 1817, their ability to govern France effectively, and restore her to her position of greatness.

The push for troop reduction gave renewed popularity to the King’s rule. Negotiating a final removal for a date prior to the stated five-year occupation program would add a further sense of stability to the Bourbon monarchy. Richelieu spent three years directing France toward a stable internal situation acceptable to the allied leadership, thus refusing to leave the Allies any valid reason for their continued occupation of France, which was formally decided at the Aix-la-Chapelle conference (October 1818). The Allies agreed to withdraw their forces by the end of November 1818 as the French government ‘had fulfilled with the most scrupulous and honourable punctuality all clauses of the Treaties and Conventions,” stated the specific document of the Aix Conference.

Aside from seeking the withdrawal of allied forces, the Richelieu government designed and then rebuilt the French army so that it was capable of insuring domestic order and tranquillity. This was another key point of the France policy, showing to the Allies the willing of Paris to be ready to guarantee the internal stability an adequate military (but not overly powerful to re-awaken Allied concerns). Internally, this renewed national pride in the French, which had suffered a crisis of image after the defeat at Waterloo. Thus, ground forces were brought to 240,000 troops in 1818 and 400,000 in 1824. Soon France was able to consider herself second in military strength only to Russia and second in naval power to Britain.

2. The Fortress Issue

The issue of dismantling the chain of fortresses that had protected France since the 18th century is an aspect not often considered in analysis of the long-term effects of conflicts during the Napoleonic period. Napoleon’s 1815 military campaign in Flanders demonstrated that the guaranteeing of the defense of the southern border of the Netherlands belonged to all Europe. The Allies included the reconstruction of the Dutch barrier fortresses, running along the current Belgian-French border, in the 1815 peace-making process. This would mean the setting up of a semi-continuous line of fortresses along the Eastern frontier of France, joining together the Rhine valley, and protecting Switzerland and the alpine side of the Kingdom of Sardinia, together with a general demolition of French fortresses.

Britain had voiced its support for an adequate military barrier in the Lowlands to the Allies in 1814. Prime Minister Lord Liverpool considered the defence of the Low Countries a “distinct British interest” of great significance. Castlereagh told Parliament “that to fortify the places in Belgium was not a Dutch object merely, but one which interested all Europe, and this country in particular.” The Morning Chronicle stated, “The fair interest of Great Britain extends no further than a secure frontier for the Netherlands, and if that can be obtained by the re-establishment of the Flemish fortresses, it is no more our policy…to promote dismemberment [of France] by which we cannot profit.”

This new guarantee became part of the overall European plan to establish and maintain order. Though the barrier forts were not the direct responsibility of the army of occupation, both devices were part of the peacemaking process and were designed to keep France within her borders. The allies would not consider withdrawal unless at least the Dutch barrier reconstruction program was completed. But the Duke of Wellington, already in 1816, along with Richelieu, agreed in principle for a reduction of the British occupation forces in consideration that the work to build the Belgian fortresses was well advanced.

The issue of the fortresses launched again a bitter diplomatic fight among the Allies, and between them and France. But France also took advantage of the division of Britain and Russia against Austria and Prussia, which failed in their attempt to force France to pay for the construction of these fortresses – a cost that was to be outside that of the general payment by Paris to the Allies.

After bitter negotiations, the Allies (always deeply divided among themselves) and France agreed to a complex mechanism with two specific protocols (one for Germany and one for the Belgian-Dutch and Savoy but against the German fortresses), which included financial payment from Paris, organizational and limited border variations with the Netherlands (Philippeville, Marienburg transferred to the Netherlands and 60 million francs to help pay for forts on the border with France). France demolished the forts in Hunningen, while the fortified city of Saarlouis was assigned to Prussia (along with the surrounding region). Prussia obtained 20 million francs for fortifications in the Lower Rhine, and another 20 for the ones in the Upper Rhine.

The rest of the 60 million, nominally assigned to the German Confederation, went in majority to Bavaria. But none of the recipients was given complete freedom of action – the construction of the fortresses in Belgium were under British supervision, while Austria and Prussia supervised the works in Germany (despite the disagreement of Bavaria), As well, Austria supervised the reinforcement of the alpine fortress of the Kingdom of Sardinia.

The issue of the fortresses saw Austria and Prussia looser (financially before than political in consideration of the use that they hoped to made of the additional war indemnity that they would want to have from France) in consideration of the lack of interest on this issue of Russia, strumentalized in its own favour by Great Britain.

3. The Arbitration Of War Payments

The extent of destruction, especially in some areas, because of military operations and occupation which went for several years, raised the issue of the war reparations as another element of the attempt to settle the conflicts of the Napoleonic wars. However, like future peace deals, the amount of war damage costs opened a Pandora Box of recriminations and furore among the parties.

The lists of compensations for the wars and occupation by French troops were submitted at the Vienna Conference. The total amount requested was immense: 775.5 million francs (Austria 200, Prussia 120, Bavaria 73, the Netherlands 65, Kingdom of Sardinia 70, Hamburg 70, Brema and Lubeck 4,5, Denmark 42, Saxony 20, Tuscany 4, Pontifical State 30, Hannover 25, Saxony and Prussia 15, Switzerland 12, Other 25).

Furthermore, Spain submitted a separate request for 263,331.912.85 francs; Great Britain, Portugal and Russia did not submit separate requests. Talleyrand first, and Richelieu later, determined to save as much of the French economy as possible, launched a strong diplomatic offensive, which closely resembled that of the future German Weimar Republic’s resistance between 1920 and 1930. Talleyrand and Richelieu outlined the impossibility for France to pay this amount without serious damage to the national economy present and future, and the risk of destabilizing the country.

Austria and Prussia put up a strong opposition – and thus the Congress was in a stalemate, which was resolved through an arbitration panel, chaired by Marshall Wellington (looking forward to the role of the US in the aftermath of WWI).

Thus, the enormous amount was reduced to a more acceptable figure (for France) of 240,664,325 francs (Anhalt-Dessau received 73,507, Anhalt-Bernuburg 350.000, Austria 25 millions, Baden 650.000, Bavaria 10 millions, Brema 1 million, Denmark 7 millions, Pontifical State 5 millions, Spain 17 millions, Imperial city of Frankfurt 700.000, Electoral Hesse 507.099, Hesse 8 millions, Hannover 10 millions, Hamburg 20 millions, Ionian Islands 3 millions, Lubeck 2 millions, Mecklenburg-Schwerin 500.000, Duchy of Nassau 127.000, Parma 1 million, Prussia 52.003.289, the Netherlands 33 millions, Portugal 818.736, Saxony 4,5 millions, Kingdom of Sardinia 25 millions, Saxony-Mainhingen 20.694, Switzerland 5 millions, Tuscany 4,5 millions, Wurttemberg 400.000, Saxony and Prussia 2.200.000, Electoral Prince of Hesse 14.000, Hesse-Darmstadt and Bavaria 200.000, Hesse-Darmstadt, Bavaria and Prussia 800.000).

This decision by Wellington, however, opened up another fracture among the Allies (the anti-French sentiment), which spread such ill-will among the claimants that Spain decided not to sign the final act of the Conference.

The sensible reduction of war payments is a key to understand the insistence of Austria and Prussia that the financial instrument of construction/rebuilding of the fortresses should be separate and not made part of the general account of French war reparations. Also, in this concern for France, both Britain and Russia emerged the winners, while Austria and Prussia were the looser. With a more manageable amount of war reparations, Richelieu’s ministry successfully negotiated loans to enable France to meet the financial obligations imposed on her and closed the dossier in the 1820, with the support of the major European banks.

Conclusion

It is a fact that the conflicts that had devastated (mainly) the European continent between 1789 and 1815 left enduring legacies, such as, the pursuit of inclusive peace, disarmament and arms limitation of a defeated power, and the establishment of mechanisms (not yet formal architectures) for consultation and political action in order to set a more stable framework.

All these were initiated on the basis of perceptions, as mentioned, of the social risk presented by the values of the French Revolution and later by a new, more powerful than ever, French attempt to establish a continental hegemony.

The example of the Congress of Vienna, and its follow-ups, despite divisions among the winners, agreed to a non-excessive punishment of the defeated and the inclusion of the defeated in a consultation mechanism, which unfortunately was not implemented and which eventually led to the Franco-Prussian war.

The lessons of the Congress of Vienna were forgotten in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war, despite the efforts of Chancellor Bismarck, whoi tried to move forward in peace negotiations in the face of hostility of the military staff and the King of Prussia and Emperor of Germany. Dire punishment of the defeated created, as everyone knows, the conditions for a new and cruel conflict forty years later.

Enrico Magnani, PhD is a UN officer who specializes in military history, politico-military affairs, peacekeeping and stability operations.

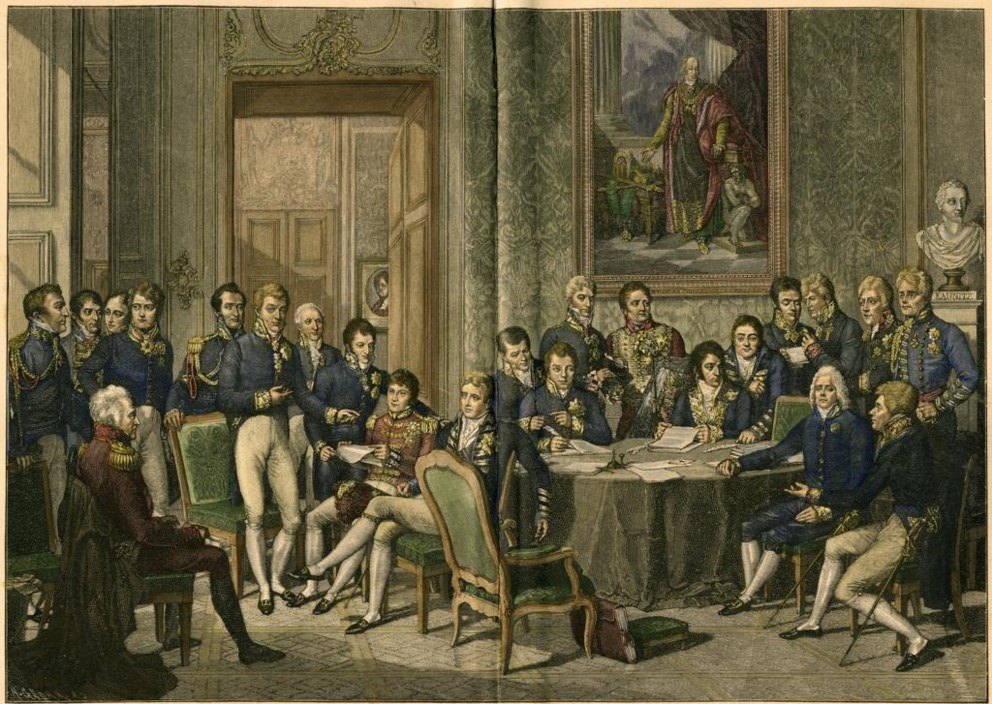

The image shows a colored engraving after a water colour by Jean-Baptiste Isabey of the Vienna Congress, 19th century.