Here I intend not only to return to topics such as essence, apodicticity, and the impossibility to deduce material existence from concept—but to address and (positively) evaluate Giovanni Pico della Mirandola’s take on the “dignity of man.” Let us start with reminding the reader that, in my approach to God, the latter is an infinite field of ideational singular models (with generic and unique properties) for singular entities (with generic and unique properties), which finds itself in presence of a (strictly) vertical time (i.e., in which past, present, and future are (strictly) simultaneous); and which finds itself unified, encompassed, traversed, and driven by a sorting, actualizing pulse that is itself ideational and which (in a strictly atemporal mode, i.e., in presence of a strictly vertical time) selects which ideational singular models are to see their correspondent hypothetical material entities being materialized at which point of the universe.

While the operation of that pulse is strictly ideational and strictly atemporal, the universe in which the ideational field incarnates itself is strictly material and strictly temporal (i.e., in presence of a strictly horizontal time, in which past, present, and future are successive rather than simultaneous). While incarnating itself wholly into the material, temporal realm, the one of the universe, God remains wholly ideational, atemporal—and wholly external to the material, temporal realm. While endeavoring to engender increasingly higher order and complexity in the universe, God is capable of mistakes in that task—mistakes which man is expected to repair in complete submission to the order that God established within the universe. Also, the atemporal operation of the sorting, actualizing pulse is completely improvisational, what leaves the universe without any predecided, prefixed direction.

The Dignity Of Man

The Mirandolian affirmation that the “dignity of man,” in essence, consists of his finding himself constrained and able to become what he freely decides to become, “like a statuary who receives the charge and the honor of sculpting [his] own person,” is not to be taken in the sense that the human being is a strictly formless, quality-less, matter who can become absolutely whatever pleases him. It is not to be understood either as the negation of the objectively beneficial or harmful character (for the accomplishment of the human being as a human) of certain things and actions.

In the Mirandolian conception of the human, the latter, instead of being completely formless, quality-less, is so only to the extent that he finds himself torn between the beast and the divine. Instead of his freedom being that of becoming absolutely whatever he wishes to become, it boils down to the one to “regress towards lower beings in becoming a brute, or to rise in accessing higher, divine things.” Instead of nothing being objectively good or bad for the fulfillment of the human as a human, certain things and actions—including temperance, the golden mean, free mind, obedience to the divine law, knowledge of the cosmic order, white magic, or literary, artistic creation—elevate him towards humanity (and thus towards a so-called “divine” character in the sense of the character of being like-divine, of being made in the image of the divine); others are degrading and change (or maintain) him into a beast, separating him altogether from his virtual humanity.

One cannot but notice the similitude with what is part of Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche’s message when he says of the human being that he is “a rope stretched between the beast and the superman;” and that such is what makes him “great.” The conception of the human according to Pico della Mirandola, that of a tightrope walker between the beast and the human-as-divine, is not less similar to what will be the one according to Konrad Zacharias Lorenz and Robert Ardrey when they say of the human, in essence, that he is free to give in to the chaotic, suffocating voice of his instincts or to impose a creative discipline on himself with the help of civilization and of knowledge.

The Mirandolian approach to the human, in which the human’s “nature” lies in its “intermediate position” between the beast and the human-as-divine, and in which the human accomplishes himself, notably, through exerting, developing his ability to think in an independent, critical mode, has nothing to do with Sartrian “existentialism,” in which the human’s “nature” lies in its absence of the slightest “nature;” and in which, nonetheless, the human accomplishes himself, notably, through complete servitude (including intellectual) in an economically communist society. It has nothing to do either with Heideggerian “existentialism,” in which the human’s “nature” notably lies in a virtual role as “shepherd of the Being” that is (according to Heidegger) as much foreign to the crowning of the cosmos through knowledge or through technique as incompatible with any high level of technical development; and in which the human is called to accomplish himself, not as the “lord of the beings” (either in a cognitive sense or in the sense of technical mastery), but as the one who muses over the mystery of the presence of those things that are.

The human’s self-accomplishment does not occur through technique stricto sensu in the Mirandolian approach to the human (which, indeed, doesn’t really address the topic of technique—to my knowledge); but it genuinely occurs, for instance, through mastery over nature in a cognitive sense (i.e., through that kind of mastery over nature that is the knowledge of nature), while said mastery is thought in Martin Heidegger to bring absolutely nothing to the human’s self-accomplishment.

In the Heideggerian approach to the human, the latter indeed occurs, notably, through meditating over the mystery that there is “something rather than nothing;” but neither through crowning the beings with knowledge nor through crowning them with high technique, which Heidegger even envisions as indissociable from the “forgetfulness of the Being.” The Being is here not to be taken in the sense of an uncreated entity that can neither escape existence (in the general sense of being) nor escape existence in an eternal mode; but in the sense of what allows for existence in existent entities (whether they’re material entities, i.e., materially existent entities) without being itself an entity. The essay will resort itself to that definition when speaking of the “Being.”

How the Being is actually articulated with the sorting, actualizing ideational pulse is a topic I intend to address elsewhere; but, in that the ideational realm incarnates itself into the material realm (to which it however remains external), the presence of the Being as a background for the ideational realm incarnates itself into the presence of the Being as a background for the material realm (while remaining external to its presence as a background for the material realm). While a property is what is characteristic of an existent or hypothetical entity at some point (whether time is horizontal or vertical), a quality is a property of a non-existential kind, i.e., a property unrelated to the entity’s existence.

A certain modality of the theory of evolution has this negative characteristic (for the spiritual elevation of the human) that it reduces the challenges of the human existence, either individual or collective, to sexual reproduction (and the transmission of genes), thus evacuating the challenge for the individual that is the preparation of oneself for the life of the soul after the death of the body.

Another negative characteristic at the level of spiritual elevation is that the modality in question reduces nature to an axiologically neutral battlefield: a land that confronts us with fierce, ruthless physical struggle for the transmission of genes (either individual or collective); but which, remaining rigorously indifferent to human existence and suffering, no more assigns to humans some end to pursue, some model of life to endorse, than it mourns their earthly misfortunes or rejoices in it. The classic axiological ideal of the pursuit is accordingly evacuated—both at the group and individual level—of a life of moderation in accordance with what is allegedly nature’s expectations: the ideal of the pursuit of the golden mean both in the individual exercise of the mental and bodily faculties—and in the group’s organization and conduct.

A golden mean that nature allegedly assigns to us, the transgression of which is allegedly at the origin of most of our earthly ills. The ideal offered in return is that of savagery and excessiveness in the “struggle for survival” and for reproduction, whether it is those of the individual or of the group: Arthur Keith noting in that regard that the “German Führer” was actually an “evolutionist,” who strove to render “the practices of Germany conform to the theory of evolution.”

That said, not any modality of the theory of evolution is actually incompatible with the classic ethics of the golden mean—in that a modality (rightly) envisioning the group’s axiological valorization, expectation, of the pursuit of the golden mean both on the individual’s part (in his individual life) and on the group’s part (in its conduct and organization) as an inescapable ingredient to the group’s success in intergroup competition for survival is actually at work, to some extent, in the considerations of “eminent evolutionists” such as Ardrey and Lorenz.

The obvious failure of Nazi Germany in the collective struggle for survival is a testimony to the degree to which a group’s imperilment expands as the group deviates from the golden mean. As for the issue of knowing whether the idea of the universe as an axiologically positioned place, i.e., one ascribing us some duties (and some proscriptions), is incompatible with any possible modality of the theory of evolution, I believe my approach to God allows to think of the universe as a place both completely positioned axiologically and—as claimed in the theory of evolution—completely neutral axiologically.

In my approach, indeed, the universe is, on the one hand, completely neutral axiologically in its existence considered independently of the spiritual realm incarnating itself completely into the universe; on the other hand, completely positioned axiologically in its existence considered as an incarnation of the spiritual realm remaining completely external to the universe. What the universe (when considered as a divine incarnation) is axiologically about is, notably, creation; and the fulfillment of creation through the human being, notably, as the latter is made “in the image of God.”

It is worth specifying that human creation (in an intellective, mental sense) occurs as much, for instance, at the level of cognition (in a broad sense covering as much art and literature as physics, mathematics, philosophy, magic, etc.) as at the level of technique; just like it is worth specifying that human creation is never so great as when it occurs in the mode of an exploit. What is here called “exploit” is a successful deed that is both exceptionally original, creative, and exceptionally risky, jeopardizing (for one’s individual material subsistence), and which is intended to bring eternal individual glory to its individual perpetrator, whether the exploit occurs on the properly military battlefield or on the battlefield between poets, the one between entrepreneurs, the one between magicians, etc.

Properly understood heroism is not about readiness to die anonymously for something “greater than oneself;” but about readiness, instead, to self-singularize and self-immortalize oneself through holding an eternally remembered life of exploit despising comfort and the fear of death. Though Pico della Mirandola rightly conceives of cognitive creation (and independence) and of the golden mean as both constitutive of the human kind’s elevation, thus reminding his reader of those ancient aphorisms that are “Nothing too much,” which “duly prescribes a measure and rule for all the virtues through the concept of the “Mean” of which moral philosophy treats,” and “Know thyself,” which “invites and exhorts us to the [independent, creative] study of the whole nature of which the nature of man is the connecting link and the “mixed potion”,” he didn’t make it clear, sadly, that the human life is never so creative, independent mentally, never so held in accordance with the golden mean, as when it is a life of exploit.

It should be added that, when it comes to the pursuit of exploit (especially in the warlike, political fields), a man’s mental creativeness, independence, his inner equilibrium, self-discipline, are never so great as in the one who, quoting Macchiavelli, knows “how to avail himself of the beast and the man” depending on the circumstances, something that “has been figuratively taught to princes by ancient writers, who describe how Achilles and many other princes of old were given to the Centaur Chiron to nurse, who brought them up in his discipline.”

To put it in another way, when it comes to war and political fight, a man is never so distanced from the beast that stands at the other end of the rope towards the superhuman as when he finds himself oscillating between the beast and the man with complete flexibility and self-mastery; a point that is regrettably absent in the Mirandolian Oration on the Dignity of Man (but, fortunately, explicit in Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli’s The Prince).

Again, Nietzsche’s message doesn’t fail to present some similitude with Florentine thinking when (in his Posthumous Fragments) he says that “at each growth of man in greatness and in elevation, he does not fail to grow downwards and towards the monster.” Whether one speaks of “transhumanism” in the notion’s general sense (i.e., in the sense of the promotion of the human being’s “overcoming” through genetic, bio-robotic engineerings), the one I will refer to in the present article (unless specified otherwise), or in the specific sense of an “overcoming” through genetic, bio-robotic engineerings that is specifically intended to emasculate the human being instinctually and mentally, the transhumanist project is obviously incompatible with the Mirandolian, Machiavellian approaches to the human (just like it is with the Nietzschean approach—on another note).

Both Pico della Mirandola and Machiavelli (but also Nietzsche) were fully attached to an ethics of exploit with which transhumanism is fully incompatible (a fortiori in the case of the above-evoked specific modality of transhumanism, which I especially addressed in a previous article); just like both (though not Nietzsche) were fully aware that the human was God-established as a worthy master of the cosmos himself put under God’s aegis, an intermediary rank that transhumanism fiercely rejects in its rebellion against the cosmic order.

Though the human is God-mandated to crown the beings with knowledge and technique, he is also God-mandated to perform his creativity in the respect of the God-implemented order and laws in the cosmos; in other words, God-mandated to accept himself as being “made in the image of God” (rather than made divine stricto sensu) and to act accordingly. None of the God-implemented laws in the cosmos can be actually transgressed; but attempt to transgress them is, for its part, not only possible but an actual cause of many misfortunes for the human.

A plane or bird can no more afford to disdain gravity (if it is to fly) than a human society (if it is to be functional) can afford to dismiss, for instance, the law of the inescapability of genetic inequality in any sexually reproducing species; the law of the instrumental necessity in any vertebrate species of “equal opportunity” for the purpose of the group’s success (in intergroup competition for survival); the law of the impossibility of (rational) central economic-planning; the law of the impossibility of (rational) central eugenics-planning; the law that what can be measured in intelligence is only part of intelligence; the law of the impossibility for the human mind to progress in knowledge (or in any field) without making use of an independent, creative mode of thinking (which is neither measured by the “QI” nor measurable); the law of the impossibility for the human mind (as it has been made by—and positioned within—the cosmos) to do any correct, precise prediction on the consequences of genome-editing; the law of the impossibility for the human mind to gather all the information required for the purpose of eugenics planning (or semi-planning) or economic planning (or semi-planning); the law of the unavoidable perverse-effects of any state-eugenics measure of a coercive, negative, or engineering kind; the law of the impossibility for the human being to master nature (to the extent possible) without submitting himself to nature; the law of the impossibility for the human being’s suprasensible grasp not to be approximative at best; or the law of the impossibility for the human being to reach some knowledge of the cosmos (or of the ideational realm) other than conjectural.

It cannot be denied that transhumanism and the afore-addressed modality of the “theory of evolution”—along with other memetic edifices of the so-called Modernity such as Marxism, Keynesianism, Heideggerianism, or Auguste Comte’s “positivism”—are part of the spiteful ideological mutations that got involved in the human’s corruption over the course of the three last centuries. Almost no longer any “positivist” dares, admittedly, to support or take seriously the notion dear to the earliest positivists, from the time of Auguste Comte, that “science,” far from requesting the slightest imagination, boils down to conducting observations (of regular causal relations) and to inducing them within theories constructed in accordance with “the” laws of formal logic; and that science provides objective certainties instead of being actually conjectural and corroborated.

The other articles of the original positivist creed—just as illusory—nevertheless remain deeply engraved in contemporary “neo-positivists.” Just as the so-called positivist spirit represents to itself that nothing exists but what is knowable (under the guise of claiming to restrict itself to knowing what is within the reach of human knowledge), it represents to itself that nothing is knowable but what is completely observable and completely quantifiable, entirely subject to a perfect and necessary regularity (at least, when identical circumstances are repeated over time) and to the identity, non-contradiction, and exclusion of the third middle (at least, in a certain respect at a certain moment). In that, “positivism” is not only unsuited to the (irremediably conjectural) knowledge of the human being, a creature subject (to a certain point) to free will, in whom everything by far is not quantifiable (or completely quantifiable); it is just as much to the (not less irremediably conjectural) knowledge of atomic and subatomic creatures, which, while behaving in a completely quantifiable mode, nonetheless remain free from the exclusion of the third middle (as highlighted by Stéphane Lupasco), perhaps even subject to their own free will to some extent (if one believes Freeman Dyson, Stuart Kauffman, John Conway, Simon Kochen, or Howard Bloom).

Positivism is equally mistaken in its conception of science as an undertaking systemically distinct from metaphysics—and in its conception of science as the key to a total human mastery with regard to nature and to an infinite liberation of his creative and exploitative powers. Just as those theories in astrophysics which relate to the beginning of the universe (including the theory of the “Big Bang”) actually tackle, in that, the issue of the “first causes,” the interest that “science” has in the allegedly necessary regularities in the causal relations between material entities (in a broad sense including atoms), what is commonly called “laws of nature,” is never more than a modality of the interest in “essences” which occupies a part of ontology.

To say of material entities that they follow a perfectly necessary regularity in all or part of their causal relations which is inherent in what they are actually falls within the discourse on “essences.” As for the mastery over the universe that science is able to bring to man, it is no more total than science is able to provide objectively certain theories. Far from science being able to render the human a god, it can only render him “as master and possessor” of nature: render him as-divine within the limits assigned to science and to the human by the order inherent in the cosmos, an order to which human submission is necessary condition for the liberation (to the extent possible) of his own creative and exploitative powers.

A scientific statement is never objectively certain nor a strict description of the sensible datum; but is instead a conjectured, corroborated statement. Precisely, what defines a scientific statement is not its object—but the fact it is conjectured, corroborated, and the way it is conjectured, corroborated (namely that is panoramically conjectured, corroborated). A claim or concept is conjectured when it is guessed from something which objectively doesn’t prove it.

A claim or concept conjectured at an empirical level (what is tantamount to saying: a claim or concept conjectured in an empirical sense) means a claim or concept conjectured from sensible experience; just like a claim or concept conjectured in a panoramic sense (what is tantamount to saying: a claim or concept conjectured at a panoramic level) means a claim or concept conjectured as much from sensible experience as from some logical laws as from hypothetical sensible impression (i.e., from sensible impression perhaps) as from hypothetical suprasensible impression (i.e., from suprasensible impression perhaps) as from hypothetical conjectures from sensible experience as from hypothetical ones from sensible impression (i.e., from ones perhaps from sensible impression) as from hypothetical ones from suprasensible impression as from hypothetical ones from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience, hypothetical other ones from some logical laws, hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression, and hypothetical other ones from sensible impression, whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else.

A claim or concept is corroborated when it is backed in a way that (objectively) doesn’t confirm it nonetheless. Corroboration at an empirical level (what is tantamount to saying: corroboration in an empirical sense) for a concept or claim means its corroboration through sensible experience; just like corroboration in a panoramic sense (what is tantamount to saying: corroboration at a panoramic level) for a concept or claim means its corroboration as much through sensible experience as through some logical laws as through hypothetical sensible impression (i.e., through sensible impression perhaps) as through hypothetical suprasensible impression (i.e., through suprasensible impression perhaps) as through hypothetical conjectures from sensible experience as through hypothetical ones from sensible impression (i.e., through ones perhaps from sensible impression) as through hypothetical ones from suprasensible impression as through hypothetical ones from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience, hypothetical other ones from some logical laws, hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression, and hypothetical other ones from sensible impression, whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else.

The logical laws used, trusted, in one’s mind are completely interdependent with the universe such as empirically conjectured in one’s mind or represented in one’s sensible impression, such as represented in one’s hypothetical suprasensible impression, such as conjectured from one’s logical laws, and such as represented in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s sensible experience, in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s (hypothetical) sensible impressions, in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from one’s (hypothetical) suprasensible impressions, and in one’s hypothetical conjecturing from hypothetical other conjectures from sensible experience and from hypothetical other ones from suprasensible impression and from hypothetical other ones from sensible impression (whether those hypothetical other conjectures are one’s conjectures or borrowed to someone else).

The scientific claims and concepts (what is tantamount to saying: the scientific theories and concepts) sometimes think of themselves as being conjectured only from the sensible datum and corroborated only from the latter; but they’re actually claims and concepts panoramically conjectured (including from the sensible datum) and panoramically corroborated (including from the sensible datum). As for the metaphysical claims and concepts, they’re neither systemically conjectured in a panoramic mode nor systemically corroborated in a panoramic mode; but, when they’re empirically corroborated, they’re also panoramically corroborated (and panoramically conjectured).

Any scientific claim or concept is panoramically conjectured, corroborated; but not any panoramically conjectured, corroborated, claim or concept is scientific. A scientific claim or concept is a modality of a panoramically conjectured, corroborated, claim or concept that not only allows for not-trivial quantitative positive predictions expected to be repeatedly verified under the repetition of some specific circumstances; but sees itself doomed to get empirically disproved in the hypothetical case where all or part of those predictions would be empirically refuted at some point.

From White And Black Magic To White And Black Technique

Technique is here taken in the sense of any apparatus intended to increase the human’s transformative or exploitive powers—whether it is through extending, sophisticating the social division of labor or through devising, deploying new technologies or through organizing society in a certain way aimed at increasing said powers. Most opponents to technique claim that they have something only against preferring technique over meditation on the Being, i.e., meditation on the mystery of the existence of things; or that they have something only against after preferring technique over the moderation of sensitive, material appetites, or over “heroism” understood as the capacity to die for one’s community or for something greater than oneself. Precisely, an error on their part lies in their more or less implicit assertion that a high level of technical development (i.e., a high level of development in all or part of the aforementioned modalities of technique) is necessarily incompatible with the meditation on the Being, the mastery of the sensitive, material appetites, or the sense of self-sacrifice—as if there were a choice to do between high technique (i.e., high technical development) and one or the other of those things.

Another error on their part lies in their more or less explicit approach to Being, the glade of existence, as a closed, complete glade, which only asks the human to meditate on the fact that there is something rather than nothing, that there is a glade rather than the night. Actually, the Being is open, incomplete, waiting for the human to pursue what exists prior to the human and to make himself the brush-cutter and arranger of the glade. Technique is no more external to the opening of the human to the Being than a high level of technical development necessarily breaks said opening. Heidegger simply failed to notice that the technique opens us as much to the Being as does meditation of the fact of existence; and that the human fulfills his role of “shepherd of the Being” as much in the astonished consideration of the presence of things as in the cognitive, technical completion of the present things. Meditative astonishment at the mystery of existence is not doomed to disappear as knowledge and technique are boarding (and prolonging) what exists; but its vocation in “the history of the Being” is to stand at the side of technical development as asked by the Being itself.

Two things, at least, should be clarified. Namely that, on the one hand, the axiological, organizational hegemony of the market (which can only be majorly at work, not completely) doesn’t lead to the axiological, organizational promotion (either complete or major) of intemperance in society; and that, on the other hand, not all technique is good technic from the joint angle of the Being, of the divine order, and of the “human dignity.” (What is bad technique from the angle of the Being is also bad technique from those two other angles. Ditto for what is bad technique from the angle of the divine order—and bad technique from the angle of the “human dignity.”)

A society that is strictly industrious in its foundations, i.e., where the industrious activity (instead of the military one) is the dominant activity in the organization and the foundational code of expectations, is not systemically a society that notably values, expects, intemperance and which articulates its industrious activity around it notably. Such society is instead a modality of the industrious society. With regard to the modality where the market is largely liberated and largely hegemonic at the organizational and axiological levels, that hegemony of a largely liberated market not only does not imply that a complete or high intemperance is valued in the foundational expectations or put at the core of social organization; but, besides, is simply incompatible with such an organizational or axiological hegemony of intemperance.

A largely liberated market notably requires (as would be the case of a perfectly liberated market) for its proper functioning the presence of (quantitatively) numerous and profitable outlets, what notably requires the presence of a virtuous circle where high levels of savings obtained notably through high or perfect temperance create—notably through a correct entrepreneurial anticipation of the respective consumption and investment demands—high levels of entrepreneurial and capital income, themselves reinjected in part into savings and in part into consumption. The modality of an industrious society where the market is largely hegemonic at organizational and axiological levels (in other words, the modality of an industrious society that is the majorly bourgeois society) is therefore a modality whose code of expectations condemns the slightest intemperance (instead of encouraging or tolerating it) and whose organization is based on high or full temperance (rather than high or moderate intemperance).

What one may call the Keynesian modality of an industrious society, where the economic system is largely based on economic policy measures whose interference with the market intentionally encourages high levels of consumption (to the detriment of levels of savings which be high or moderate), is actually a modality that axiologically praises high intemperance notably and which notably relies on it in the organization; but that modality, precisely, is neither one where the market is majorly (or completely) liberated nor one where it is majorly (or completely) hegemonic in values.

It is true that a society where the market is majorly hegemonic (both organizationally and axiologically) is a society where the valued, expected code of conduct in the foundations of said society includes—apart from self-sacrifice on the battlefield in intergroup warfare—concern for pursuing as a priority, placing above all else, a perfectly temperate and perfectly responsible subsistence, which be so long as possible and which avoid danger as much as possible; but intemperance, whether high, complete, low, or moderate, is just as incompatible with such code of conduct as (strictly) high or complete temperance is indispensable to the organization of a society where a largely liberated market is largely hegemonic.

Just as the bourgeois code of conduct and indulgence with regard to such-or-such level of intemperance (were it the lowest) are wholly distinct (and even wholly incompatible) things, a (completely) Keynesian market and a widely liberated market are wholly distinct (and even wholly incompatible) things. Just as a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires quantitatively numerous and profitable outlets for its proper functioning, it requires qualitatively numerous and profitable outlets: in other words, profitable outlets that are “diverse and varied” (rather than homogeneous). It is not only false that a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires for its proper functioning a (strictly) complete or high intemperance; it is just as much false that a largely liberated and largely hegemonic (axiologically and organizationally) market requires standardized outlets for its proper functioning.

Whatever the level of liberalization of the national or global market, a double cause-and-effect relationship that is at work both in the national and global market is effectively the following. Namely that the more the profitable outlets are qualitatively numerous (i.e., diversified at the level of their respective attributes), the more they are quantitatively numerous; the less they are qualitatively numerous, the less they are quantitatively numerous. The highly standardized character of goods and services in the contemporary global market is precisely a dysfunctional pattern in the globalized market; and that dysfunctional motive is itself the consequence of the fact that, however globalized it may be, the globalized market is largely hampered juridically—and hampered for the benefit of a narrow number of companies and banks enjoying fiscal and legal advantages that are such that those companies and banks are largely sheltered from competition. Both at the national-market level and at the global-market level: the more competition is juridically locked, the less the profitable outlets are qualitatively, quantitatively numerous; the less it is, the more they are.

Just like a society that majorly prefers technique over exploit, i.e., which majorly disdains exploit for the benefit of technique, is majorly detrimental to the human’s elevation towards the superhuman, a society that completely prefers technique over exploit (as is the case of a majorly bourgeois society—and as would be the case of a completely bourgeois chimerical society) is completely detrimental to the human’s elevation towards the superhuman. Technique is not more to be preferred (completely or majorly) over exploit than the latter is to be preferred (completely or majorly) over the former. Both are compatible and should go hand in hand (as is the case in some modalities of a society completely warlike foundationally). Yet the opponents to technique err not only in their amalgamating disdain for heroism with disdain for temperance; but in their understanding heroism as a conduct incompatible with (high) technique—and as a conduct turned towards self-erasure and self-sacrifice through anonymous death (even while heroism is really about self-singularization and self-immortalization through exploit such as defined above).

What’s more, they fail to notice that the problem with technique is not only to be aware not to prefer technique over that to which it should remain not-preferred; but to be aware not to indulge into what can be called black technique or bad technique (in comparison with that kind of magic that can be called black or bad). Precisely, the distinction that Pico della Mirandola takes up (and clarifies) between two kinds of magic, the one which “entirely falls within the action and authority of demons” and the one which instead consists of “the perfect fulfillment of natural philosophy,” must extend to technique. Namely that, while the good, white technique is the one which is only the crowning of the natural order, the completion of the Being, the bad, black technique is the one which (were it unwittingly) works to transgress the natural order, subvert the Being. The former contributes to fulfilling the human as a being-as-divine, but the latter, working (were it unwittingly) to render the human divine, contributes to corrupting him and handing him over to the demons. The former really institutes the human as a fortunate co-creator alongside the divine, but the latter, indulging in the chimerical project of escaping the cosmic order and equaling the divine, only makes to condemn the human and his work to misfortune.

Just as bad magic, to quote Pico, is, rightly, “condemned and cursed not only by the Christian religion [of the type of Catholicism of Pico’s time], but by all laws, by every well ordered state,” the bad technique must be legally, politically, religiously condemned unambiguously. The transhumanist, so to speak, must be led to the stake just like the Keynesian. From engineering on the genome of embryos to those neuro-robotic implants undermining free will, from genetic planning to any coercive, negative, or engineering state-eugenics measure, from economic planning to any economic-policy measure undermining such things as inheritance, free competition, saving, or the freedom itself to do saving, demonic-type technique must be banned in its entirety; but good technique, the one which elevates us towards God and the superhuman, must be authorized.

Grégoire Canlorbe is an independent scholar, based in Paris. Besides conducting a series of academic interviews with social scientists, physicists, and cultural figures, he has authored a number of metapolitical and philosophical articles. He also worked on a (currently finalized) conversation book with the philosopher, Howard Bloom. See his website: gregoirecanlorbe.com.

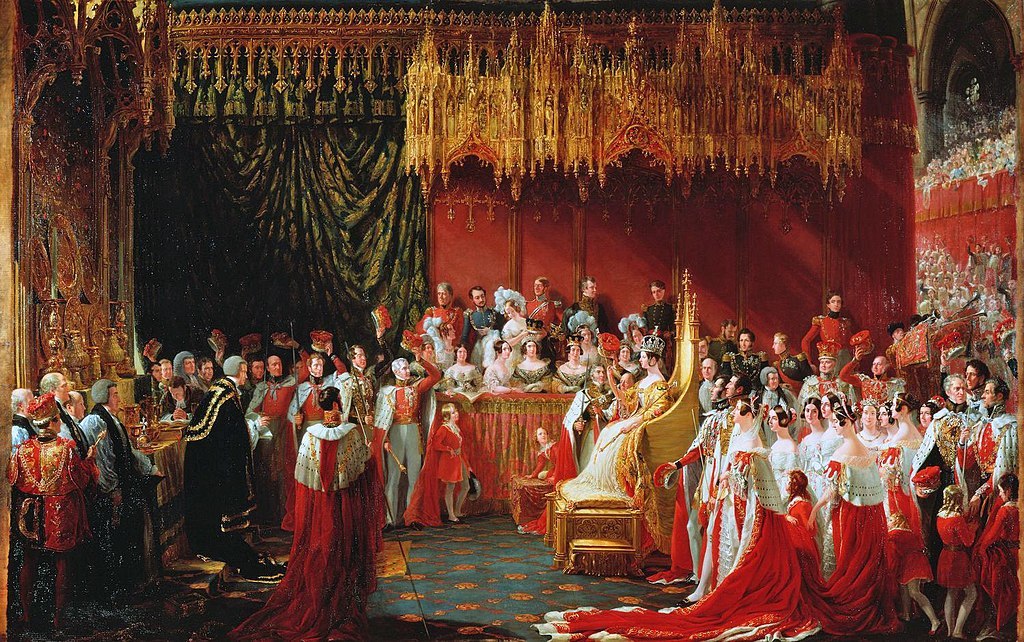

The featured image shows, “Herod’s Banquet,” by Filippo Lippi; painted ca. 1452 and 1465.