Chris Farlowe, Rod McKuen, Colin Blunstone and Clifford T. Ward aren’t exactly celebrities; the sole exception is McKuen who nonetheless died relatively obscure and unjustly patronised. The first three have remarkable voices in utterly different ways, whilst the fourth was a singer/songwriter of minor genius.

McKuen was a later discovery for me – he was never particularly big in Britain, and is probably the guiltiest of these pleasures. Only Farlowe had a Number One, a record that remains, alongside “Bridge over Troubled Water,” “Dancing Queen” and “(Too-Rye-Ay) Come on Eileen” (but not “Hey Jude”), one of my favourite tops of the pops.

This happened the week that England won the 1966 football World Cup, to the delight of Mr and Mrs Broadbridge, teaching Germany another lesson lest they forgot. The song in question was “Out of time,” a Jagger/Richards composition which from the opening strings playing those stirring chords, you know would be a winner.

The lyrics address a tiresome ex-girlfriend who needs to be told she’s so last year:

You don't know what's going on

You've been away for far too long

You can't come back and think you are still mine.

You're out of touch, my baby

My poor old-fashioned, baby

I said, baby, baby, baby, you're out of time.

Poor thing! Farlowe has been labelled a one-hit wonder but several singles made the lower chart reaches and the album “The Art of Chris Farlowe” (and it was art) sold respectably. “Ride on baby,” which had nothing to do with lawnmowers, was too much of a carbon copy to succeed, but an earlier Jagger/Richards song, “Think,” should have been a lot bigger.

Farlowe is white, but he definitely sounds black. His voice tends towards the rasping and gritty, it’s tough, it makes no attempt whatsoever to endear or charm, which is part of his integrity but does nothing for his popularity. Nor is Farlowe’s stage presence or appearance heart-warming: with his narrow set eyes and long nose, he looks like a lean 1960s London gang leader who would either have beaten up Francis Bacon, or would have been requested to do so with cash inducements.

Farlowe later got into strife for selling Nazi regalia in his antique shop, compounding the image problem, and yet when you see him on rare video footage sharing the stage with his idol, Otis Redding, he commendably holds his own. He’s a good match for the Father of Soul James Brown himself in his rendition of “It’s a man’s world.” But the title: can you see the problem? He doesn’t shake hands with our heart, so much as stomp on it. “We’re doing fine” drips with relationship tensions:

Everybody wants to know

If everything's alright

I guess they thought by now

We'd had a great big fight

No no no no no…

Farlowe protests too loudly. The grim way he sings it suggests that a rather horrible fight had indeed taken place, or else was highly likely to do so. Years later (1988) guitarist and Pre-Raphaelite art collector extraordinary, Jimmy Page, plucked Farlowe out of relative obscurity to sing several tracks on his album “Night Rider.” Page has always had impeccable taste and knew what he was doing. “Hummingbird,” a Leon Russell cover far superior to the original, shows that Farlowe had lost none of his old tricks:

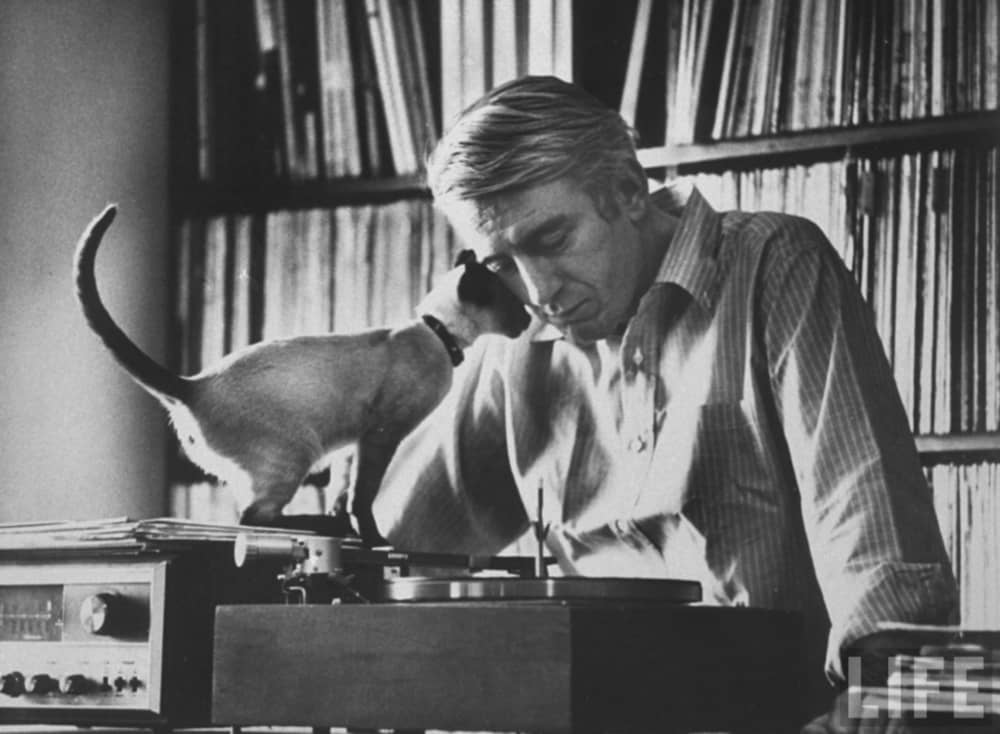

The gulf between Chris Farlowe and Rod McKuen is akin to blue cheese bordering on rancid, and strawberries and cream. Rod is an old flirt, a cardigan clad charmer, at least in his now rather excruciating TV specials which were hugely popular in North America half a century ago. Yet his songs about love and loss are something else: melancholy, sometimes even bitter. Oh, that husky, raspy voice! Technically it is god-awful, and came about after Rod had irreparably wrecked his vocal chords in 1961. But like our friend Bacon painting the backs of his canvases, Rod shrewdly made a virtue out of this.

If you like the overpraised Tom Waits, you can’t credibly dislike Rod, and I would even say much the same about Leonard Cohen. Yet Rod seems destined to go down in history as “the king of kitsch” and it was a sad reflection on today’s philistinism that his vast personal archive was scattered and sold, rather than acquired by the Harry Ransom Center…

You “Rodophobes” should look at yourselves. You people would protest, but you’re the victims of left-liberal genre and cultural snobbery. You can’t even claim the high moral political ground, for Rod’s liberalism was impeccable and his fight for gay equality utterly laudable. He famously combined his composing and performing with poetic aspirations, and the slim volumes which now turn up in car-boot sales, perhaps accompanied by their late owners’ lava lamps and kaftans, once sold in millions.

Many people’s minds—and I would venture to say not a few ageing academics’ minds—were opened up to poetry thanks to Rod, but he has received singularly little thanks for this. He’s a bit too homespun, predictable and lower middlebrow, a wannabe Charles Bukowski. Posterity, as I say, has been ungrateful, but a poetic sensibility unquestionably infuses Rod’s many memorable songs.

Some of the best are tributes to Rod’s Belgian mentor and friend Jacques Brel, which he translated. The much-recorded ‘If you go away’ is something of a signature song, surpassing almost every other cover version (no thanks, Neil Diamond):

If you go away on this summer day

Then you might as well take the sun away

All the birds that flew in a summer sky

When our love was new and our hearts were high

When the day was young and the night was long

And the moon stood still for the night bird’s song

If you go away, If you go away, If you go away…

I know, I know. My personal favourite is “Seasons in the Sun,” the reflections of a dying man. Please ignore that Canadian Terry Jacks’s icky and cheesy cover, and instead appreciate Rod’s mordant and angry rendition. Its poignancy is accentuated by the barest of acoustic guitar accompaniment and you don’t forgive or forget the cheating Françoise easily:

Rod could of course write (and perform) no shortage of admirable songs in his own right. Frank Sinatra knew what he was doing in recording “A Man Alone,” an album entirely based on McKuen, and not unusually it is rated far more highly by popular opinion than by jaded critics. “Love’s been good to me” is the standout track and Rod’s version holds its own against the infinitely greater formal perfection of Sinatra’s singing. Rod may have gone away, but his brittle talent and charm live on for me at least:

Like many people, I sometimes fantasise about singers, what they might be like and what their intellectual pursuits might be. With the late Robert Palmer, so studied, stylish, sophisticated, suave, witty and ever experimental, I felt that he must have enjoyed the fiction of Sterne, Thackeray and possibly Gide. No such luck: he was evidently at his happiest getting up at night and working on his Airfix model aircraft kits (just as Rod Stewart famously loves his train set). Perhaps my illusions would be likewise shattered by any putative meeting with Colin Blunstone.

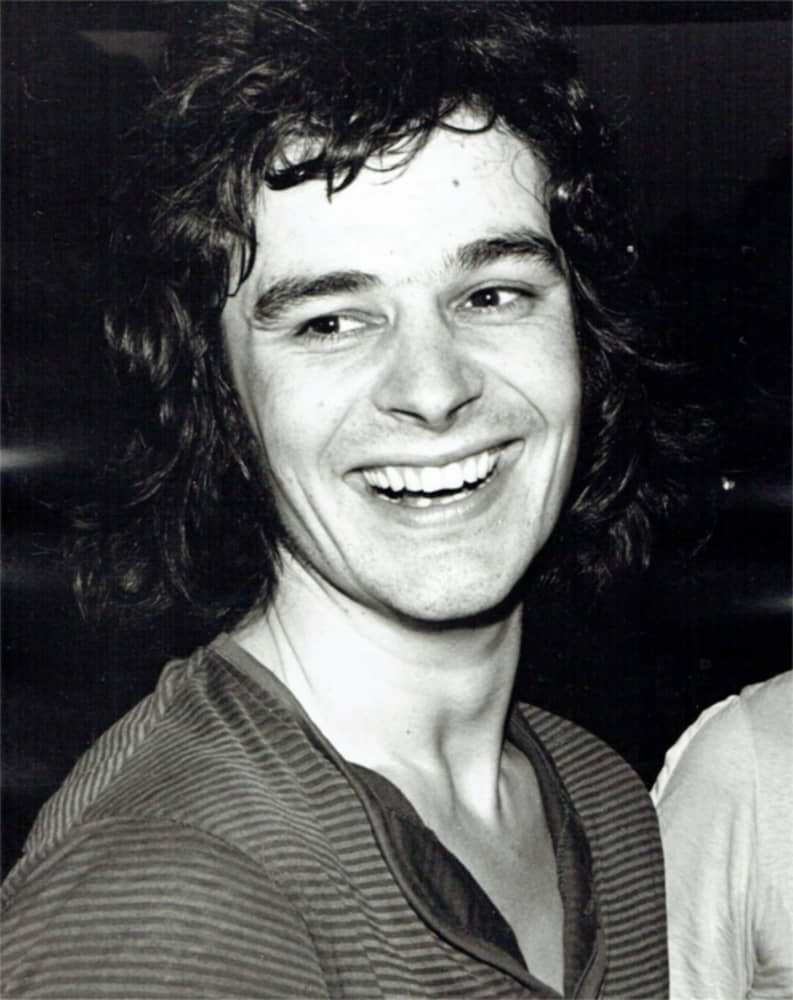

When I listen to his singing, I feel he is incapable of the common, vulgar, unrefined or uncouth. This is a voice which, before it broke, would have surely made him head chorister at the local St Albans Cathedral or even one’s alma mater, King’s College, Cambridge. The same adult voice was an integral part of the appeal of the Zombies, those pioneers of Prog, whose breathily beautiful “She’s not there” and “Time of the season” were surprising but deserved chart toppers in the US. American audiences are far less familiar with, but would surely not be disappointed by, Colin’s solo career from the early 1970s onwards. Here, Prog yields to superior, sensitive pop. I remember one of my contemporaries in the sixth form (11th grade) describing how he had been reduced to tears by “Caroline goodbye”:

Saw your picture in the paper

My, you're looking pretty good

Looks like you're gonna make it in a big way

Oh, I always knew you would

But I should have known better, yeah

And I should’ve seen sooner.

There's no use pretending

I've known for a long time your love is ending

Caroline goodbye

Caroline goodbye.

It’s that emotional generosity moving me (and my mate), perfectly meshed with that perfect sounding tenor. How could anyone in their right minds chuck Colin, who is as good looking as that voice? And it would be Caroline (a classy name half a century ago), rather than Sharon or Tracey: Colin, you are middle-class Home Counties and I like you very much for that.

Colin’s biggest hit was a cover of Denny Laine’s lovely song “Say you don’t mind” (I remember a music critic remarking how he would immediately smile whenever he heard it playing). Colin’s tenor attained powerful falsetto heights, corresponding yet again to the emotional… tenor. Oh, and those strings!

I realise that I've been in your eye some kind of fool

What I do, what I did, stupid fish I drank the pool

I've been doing some dying

Now I'm doing some trying

So say you don't mind, you don't mind

You'll let me off this time.

I forgive you anytime, Colin, but I can’t speak for Caroline. The voice is perfect, the songs likewise, and sometimes quite complex (“How can we dare to be wrong?”) and I continue to remain as baffled as I was half a century ago as to why he wasn’t a megastar:

How could people “fail to see” as Colin rhetorically asks in this song? But I get the strong impression that Colin is relaxed and contented with the recognition that he does get, and again he has my admiration. In fact, I feel a fan letter coming on:

Dear Mr Blunstone,

I’m in my 60s and average looking. I like church architecture and Prog Rock and like you grew up near St Albans. Well, I’d like to tell you that for many years, I’ve just loved your singing and your songs…

Next singer, please!

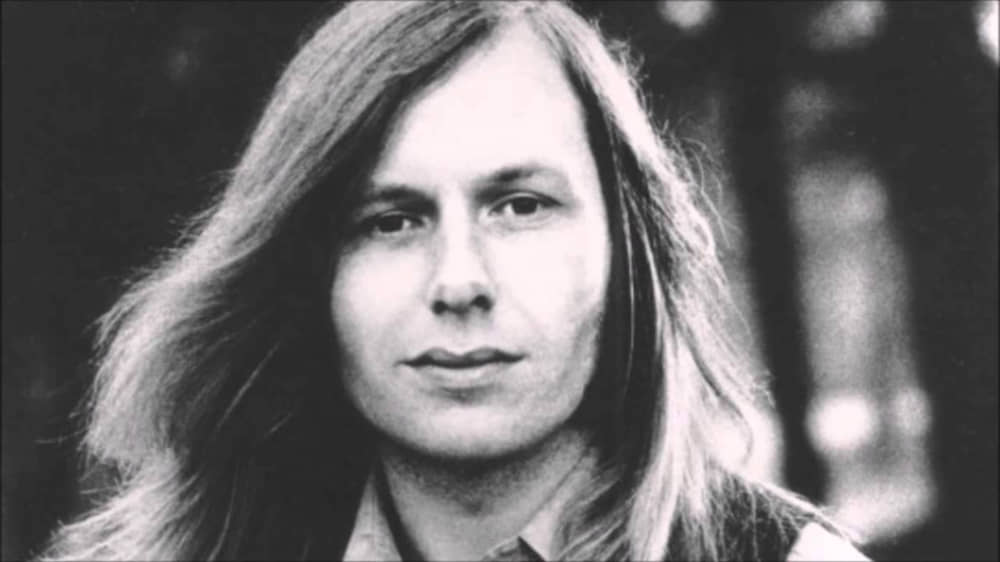

As one of Clifford T. Ward’s obituarists has observed, his best songs—and there were a fair few—synthesised a fine grasp of pop melody with genuine poetic sensibility. An awful lot of English art before those ghastly, self-advertising Young British Artists, and a comparable amount of literature, celebrated the homely, the domestic, the everyday and the low-key. Woe betide anyone who mistakes this for insipidity.

Ward epitomised these qualities. He first hit the charts as a Worcestershire schoolteacher with “Gaye,” which enchanted me as a sensitive and uncertain 17-year-old, and no, it is not about liberation of one’s sexuality. But my personal favourite has to be “Scullery.” North American readers perhaps need to be told that this is an offshoot of the kitchen in an English home, where you wash your smalls or dirtier pans. Clifford T’s perfect enunciation perhaps makes any reproduction of his lyrics otiose, but I hope you too marvel at how he makes the humdrum poetic:

You're my picture, by Picasso

Lighting up our scullery

With your pans and pots and hot-plates

You'd brighten up any gallery

If I could paint a different picture

Leafy lanes and flower scenes

Buttermilk, your cooking mixture

You still have ingredients that make you shine

And when you take your apron off I know you're mine…

This was inspired by his wife, Pat, whom he knew from their schooldays. One would love to create an idyll around them and their four children living in a picture-postcard ivy-clad cottage, but the reality was far sadder. Clifford T. was diagnosed in his early forties with multiple sclerosis, and took many years to die.

From his stage persona, he seems the very embodiment of sensitivity and sweetness, but a tell-all biography sadly blew that image to smithereens and though this was surely aggravated by pain, he emerges as hectoring and self-centred. Yet, to quote Prog Rock band the Nice, ars longa vita brevis, and there remains much to cherish in Clifford T’s songs. “Home thoughts from Abroad,” itself of course a quotation from Robert Browning’s famous poem, and the gorgeous “The best is yet to come,” are both cases in point:

Obviously, Clifford T. had no truck with punk rock, and the feeling was mutual.

Truly, he could be deemed a cult figure: his shyness meant that he loathed live performance, and yet he and Pat were legendary for making fans cups of tea if they called round. This was utterly in character with the aforementioned domesticity and decency. I’d like to think the same fans would go on to do brass rubbings in a local church on the same trip, but I fantasise.

People who matter in music jolly well knew he was special: these included Elton John (“Your song” is very Clifford T), Paul McCartney, whom historian Dominic Sandbrook rightly lauds as the greatest Beatle, while Justin Hayward of the Moody Blues, Art Garfunkel and Judy Collins all recorded cover versions of his songs. Clifford T. died aged 57 in 2001 and I am pressing for his inclusion in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Mark Stocker is an art historian whose recent book is When Britain Went Decimal: The Coinage of 1971.

Featured image: “Colin Blunstone-The Zombies,” by Thomas Leparskas, 2020.